#102: Digital identity and industry contributions: lessons from India, Australia, and Brazil

W FINTECHS NEWSLETTER #102: 08/04-14/04

👀 Portuguese Version 👉 here

This edition is sponsored by

Iniciador enables Regulated Institutions and Fintechs in Open Finance, with a white-label SaaS technology platform that reduces their technological and regulatory burden:

Real-time Financial Data

Payment Initiation

Issuer Authorization Server (Compliance Phase 3)

We are a Top 5 Payment Initiator (ITP) in Brazil in terms of transaction volume.

💡Bring your company to the W Fintechs Newsletter

Reach a niche audience of founders, investors, and regulators who read an in-depth analysis of the financial innovation market every Monday. Click 👉here

👉 W Fintechs is a newsletter focused on financial innovation. Every Monday, at 8:21 a.m. (Brasília time), you will receive an in-depth analysis in your email.

From developing to developed countries, not being able to confidently answer the question "Who are you?" can limit a person's participation in society. According to World Bank data, around 850 million people lack an official identity. The lack of identity is considered by the FATF as one of the barriers to financial inclusion, where of the 1.7 billion unbanked adults worldwide, 26% cite lack of documentation as the main barrier.

Not surprisingly, as mentioned in edition #100 (available 👉 here), some countries have focused on establishing a national plan for the development of their digital infrastructure. In India, the success of India Stack was due to the digital identity layer called Aadhaar, launched in 2010, which established itself as a unique 12-digit identifier to authenticate individual identities. Currently, over 1.2 billion Indians have a unique digital identity through the system.

The industry has also been moving and taking advantage to promote more security and, primarily, increase efficiency in user identification and fraud prevention. There are two interesting cases: one based on a decentralized identity model promoted by Caf to reduce fraud, especially due to deep fakes and advances in generative artificial intelligence; and another is an intelligent registry that, using Open Finance data, reduces frictions and improves user onboarding in financial institutions, offered by the Iniciador.

The pillars of identity

In the last century, the identification landscape was much more complex than it is today. Technology has increasingly assisted in the collection, processing, and storage of data, ensuring the integrity of identification systems. In many cases, tools such as biometrics, smart cards, and/or public key infrastructure are being used to protect user credentials.

When considering existing identification systems, they often have not reached their full inclusion potential due to two main aspects: (i) despite progress in some parts of the world, many people still lack formal identification, especially in regions with high rates of extreme poverty, such as in Africa and South Asia. This is due to difficulties in the registration process, i.e., reaching these individuals in remote areas of the country with poor access to technology; (ii) additionally, national identification systems often fail to fulfill the vision of their creators, either because they are not well integrated into service provision or because they fail to create compelling use cases for users.

The value chain of digital identity

Digital identification systems comprise three distinct phases: registration, authentication, and authorization. Each stage has its complexity. In countries where there are many regions with underdeveloped digital infrastructure and a high poverty rate, international experience has shown that identity providers face more difficulty in progressing from the registration stage.

This is because the way registration can be conducted requires not only high technology but also a concerted effort from various stakeholders, as well as societal trust in the system. In India, for example, the implementing entity managed to overcome this challenge by strategically distributing registration centers across the country, making agreements with the private sector to reduce the costs of necessary equipment, and establishing inclusive guidelines in the system's design to ensure that all individuals were included.

The registration process involves several stages, such as identity verification, which associates records with a real person by verifying unique and stable attributes over time - some systems use biometrics combined with biographical data. Each identification system has specific requirements, which may involve using original documents or even a trusted individual where such documents are scarce, as in the case of India. International experience shows that collecting information to ensure distinction among registrants is crucial, primarily to enhance system reliability.

After presenting the identification credentials, the authentication stage begins, which checks in the database whether the information matches. This process involves a combination of three types of credentials: something you have (like an identification card), something you know (a PIN), and something you are (biometric data).

Following authentication, an authorization database matches the credentials with information about which services each user can access. This step ensures that only authorized users have access to specific services or resources according to established policies. For example, it can verify if the identity document holder is over 18 years old or is a local resident.

Different ways of designing and building systems

Some countries have different identification systems, serving distinct purposes and issued by different authorities, complicating interoperability. As a result, providers face significant challenges and costs when adapting these systems to new needs.

The literature differentiates between two types of identity systems: functional and fundamental 1. Functional systems are created for specific uses, such as obtaining a driver's license or paying taxes, while foundational ones aim to provide identity as a public good, enabling more integrations and use cases. It's also important to differentiate the concepts of civil registration and civil identity.

For example, India aimed to create a true platform with Aadhaar, which today, through APIs, can be easily integrated, enabling its use across various services and sectors.

In other countries, the use of functional identity systems in a sector different from the one for which they were designed can be challenging, as each sector has specific needs that the system may not fully encompass.

For instance, in healthcare or electoral purposes, the need for information varies, from more sensitive data to determining if the person is eligible to vote. However, for opening bank accounts, identification accuracy must be even stricter, especially due to international regulations on combating money laundering and terrorism financing.

How have international experiences been?

Although the centralized model is the most widely used, there are other classifications of models that are independent of whether the identity is digital or not, such as the federated model, where different organizations trust each other to accept issued identities. In the decentralized model, each user maintains full control of their own identity data, without relying on a central authority for its management.

One thing I found interesting while reading and talking to some people in the identity market was observing how countries diverged and encountered difficulties in creating their identification systems. Asian and African countries, undoubtedly, faced the most challenges in this aspect — and today are regions with the highest number of people without identification, according to World Bank data 2.

In Latin America, I confess I was surprised to discover that our identification rates are higher (0-15% of the population have no record), except in Bolivia and Paraguay, where 15-30% of the population has no record. Despite the economic challenges that Latin America also faces, social programs have driven advances in population identification, especially during and after the Commodities Boom in the transition of the century. This expanded the reach of government identification systems, although it has not completely solved the problem.

In Asia and Africa, concern about identification has gained even more strength in recent decades. Despite economic growth in some countries in these regions, many have not benefited because they are not visible to the government and, consequently, have been excluded from social programs.

India managed to overcome these challenges by implementing a system that enabled the creation of various additional services — such as payments, data sharing, etc. — resulting in a true digital ecosystem. In Kenya, the government also attempted to address the challenge of creating an identity system, called Huduma Namba or the National Integrated Identity Management System (NIIMS); however, after millions of dollars in investments, the system was discontinued because it failed to integrate with other services and lost the trust of society. The Kenyan government is now focusing on a new system that is more foundational, meaning it can deliver more benefits to users. In Colombia and Mexico, there are also advanced discussions on modernizing identification systems, primarily aiming at the digital economy and combating fraud.

India 🇮🇳

Until 2009, India lacked a recognized national identification system; Indians carried various identification cards for different government purposes, such as taxes, food subsidies, and basic services, without a single valid document for all purposes nationwide. With a population of 1.3 billion people and 22 official languages, the rapid economic development of recent decades did not benefit much of the population. In 2010, 40% of the population lacked birth registration, 30% were illiterate, and 60% did not have a bank account. Only 3% paid income tax and only 60 million had passports 3.

The government at the time realized that a unique identification system could reduce costs, prevent fraud, and provide identification for millions of Indians for the first time. Initially, the government invested $13 million in creating the UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India), tasked with implementing Aadhaar, and appointed Nandan Nilekani, an executive from Infosys, to lead the project. Aadhaar's main goals were to promote digital inclusion and serve as a fiscal tool for government programs.

To identify over 1.3 billion Indians, UIDAI adopted biometric deduplication, using 10 fingerprints, iris scans, and a facial photograph to digitally represent each individual. To garner national consensus and overcome political instabilities, Nilekani established a vast network of contacts, including ministers, bureaucrats, the Reserve Bank of India, and multinational companies. With a simple design, UIDAI created a partner ecosystem, establishing around 35,000 enrollment centers nationwide and hiring various suppliers to launch the project.

In four years, Aadhaar issued 600 million identifications, significantly surpassing the initial target of 100 million users. Estimates suggest the system costs less than $10 per person, covering over a billion people, with a total production cost between $10 billion and $12 billion.

But it wasn't all smooth sailing for Aadhaar, which faced discussions regarding the privacy and security of Indians' data after the numbers, names, addresses, and bank account details of 1.4 million people were accidentally disclosed by a state Social Security office. On another occasion, an Indian newspaper, The Tribune, revealed that it was able to purchase personal information from the Aadhaar database for $6 via WhatsApp, all of which brought more concern to the creators.

The government responded by allowing users to generate and use virtual IDs instead of Aadhaar numbers and implemented federated databases to keep the information separate for each service. In other words, instead of providing the 12-digit Aadhaar number, which is linked to biometrics, the individual can request a virtual Aadhaar identification number to provide to each company they wish to engage with.

Several key points were essential to Aadhaar's success, including:

Collecting little information and focusing on the problem;

Choosing a reliable and inclusive design;

Focus on data privacy;

Creating a digital ecosystem based on identity.

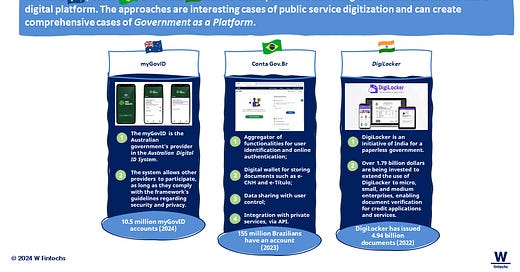

These pillars enabled Aadhaar to take off and encompass over 3,500 government and non-governmental services in India, ranging from opening bank accounts to conducting digital payments, school enrollment, and voting. The country also created DigiLocker, a type of document wallet that provides cloud space for Indians for the issuance and digital verification of various documents such as vehicle documents, and voter IDs, among others. The government believes that the potential of Aadhaar has not yet been fully realized and has been betting that through the APIs offered by the system, the private sector will drive its growth. Aadhaar is an example of a foundational system designed to work in the long term, which recognizes the power of cooperation as a disruptive force.

Australia 🇦🇺

In Australia, the Australian government created Australia’s Digital ID System, a secure way to verify citizens' identity online. The system facilitates access to services, as it does not require excessive sharing of personal information, simplifying processes such as renting a property or signing up for a new phone plan without the need to share copies of identification documents.

The system is federated, so each user can choose from various providers, both governmental and private, who they want to manage their digital identity. The government is one of the participants as an identity provider, with the myGovID. According to the Australian government, the system does not replace physical documents but complements them, providing a simple and secure way to verify identity online.

To create it, the government established the Interim Oversight Authority responsible for the operational assurance of the system, which oversees compliance with the Trusted Digital Identity Framework (TDIF). This framework establishes rigorous standards for privacy and security in the management and configuration of identities, ensuring the reliability of services.

During digital ID setup, users provide their identification details, as shown in the flow below, which are digitally verified by providers in collaboration with issuing authorities. Once verified, the digital ID is created, enabling access to online services, while users share only necessary and consented information.

The key lessons from Australia's experience are that cooperation among trusted players and regulators, along with the establishment of a common framework defining data privacy and security guidelines, are fundamental characteristics from the outset. However, to further expand the system's reach, a larger network effect is necessary. In other words, the more organizations accept and use digital identification, the greater the incentive for people to adopt the system. Some experts have pointed out that due to the complexity and accreditation cost for providers, there is little industry interest, although giants like Mastercard are involved.

Brasil 🇧🇷

In Brazil, there is a variety of documents recognized as legal identities, each issued by different government agencies. For example, the Identity Card (RG), issued by the Public Security Secretariats of the states, is the most commonly used as proof of identity and even allows the issuance of other identification documents. In addition to the RG, the country has the National Driver's License (CNH), issued by the Department of Traffic (Detran), and the Passport by the Federal Police, among others. There are also administrative registries, such as CPF (Individual Taxpayer Registry), NIS (Social Identification Number), CadSUS, among others.

The existence of various documents has resulted in different databases, making interoperability difficult and posing a huge challenge for public management, which needs to consolidate or cross-reference information from different databases to try to prevent fraud in services, for example.

The RG also poses several challenges. Since it is issued in different states and there is no centralized registration system among these agencies, there are more cases of fraud and fake identities, as a person can obtain a different identity card in each state (even using false data) and try to access the same public service more than once.

For decades, there have been initiatives to unify databases in Brazil. A recent advancement was the creation of the National Identity Card (CIN), which, starting in January 2024, incorporates the CPF as a unique numerical identifier. The CIN is available in both physical and digital forms and has an official process for issuance and data registration nationwide, eliminating the use of divergent information in citizen identification.

In 2020, the government also created the Conta Gov.BR to serve as an aggregator of functionalities for online user identification and authentication. This includes a mailbox for notifications from public agencies, a digital wallet to store documents such as e-CNH and e-Titulo, data sharing with user control, and integration with private services such as banking services that could automatically fetch user data through APIs, among others. I believe this approach resembles the Australian system and the Indian DigiLocker, although Brazil has not opened the system to other identity providers, as Australia has done.

The digitization of public services in Brazil, with initiatives like the Conta Gov.BR and the CIN, represents significant advancements in transforming identification in the country towards a more digital form. I believe we can move towards something similar to India Stack, combining Open Finance, Pix, and the Brazilian digital currency into a single interoperable ecosystem. However, before that, we need to increasingly consider the government as a platform, meaning a set of public services available for the industry or the public sector itself to develop new solutions.

How has the industry been involved?

In addition to government efforts to create increasingly reliable identification systems, the industry has also directly contributed to streamlining the identification process. For example, in 2023, Apple announced that starting with iOS 17, American companies could accept IDs in Apple Wallet. This means that iPhone users can present their driver's licenses or identity documents stored in Apple Wallet at participating businesses and locations. Verification will be done directly through the company's iPhone, eliminating the need for additional hardware. Users simply need to tap their iPhones or Apple Watches to confirm their identity.

With the growth of online transactions, there have also been more challenges in verifying a person's identity, further expanding the space for the growth of Know Your Customer (KYC) companies. Valued at $8.6 billion in 2021, the global identity verification market could reach $18.6 billion by 2026.

I believe we are in an interesting moment in the global identity market, where two things can change the rules of the game: decentralized technologies and Open Finance.

Decentralization and Open Finance

The increase in fraud, including with generative artificial intelligence and deepfakes, has demanded even more innovative solutions to ensure security and compliance. For example, the Central Bank of Brazil published Joint Resolution 6, requiring regulated financial institutions to share data on fraud indicators to reduce banking fraud.

One Brazilian company that has positioned itself well in providing a solution for this is Caf, a B2B company whose clients are consumer-facing and they use the All.id platform, a decentralized identity network. Caf's All.id functions as a shared network based on distributed ledger technology (DLT), where each participant maintains its own network infrastructure but is connected to a common network. Based on a decentralized identity infrastructure, organizations can securely exchange identity information through the All.id platform.

In practice, users request identity verification through a partner app, which sends anonymized data to the All.id network. The network then searches for a corresponding identity model, requesting responses from each available node. An All.id service compiles these responses into a single one and sends it back. The decentralized model ensures that anonymized data is stored at each node, avoiding central repositories. This decentralized approach reduces the risks of data breaches and streamlines identity verification for businesses. The platform ensures quick and accurate verification while maintaining compliance with global data protection regulations.

In Open Finance, you can also find other innovative KYC solutions. Driven by regulated data sharing with prior user consent, Open Finance has helped various companies create a faster and simplified onboarding process. Plaid, a B2B company providing an Open Banking platform, has been doing fascinating work, creating a "check once" experience that allows for quicker verification while maintaining compliance with KYC.

In Brazil, Iniciador, a Brazilian B2B company providing an Open Finance platform for banks and fintechs, has accelerated identity verification using users' banking data. Through the Cadastro Expresso (Quick Registration) product, it's possible to bring customer information already validated by financial institutions in just 2 clicks and without the need for manual inputs. This reduces friction in onboarding and strengthens security against fraud by making it difficult to use false or stolen information to open fraudulent accounts.

Thoughts for a more interoperable future

The lack of a reliable identification can exclude individuals from society. I believe identification is based on a dilemma: not having identification can result in social exclusion, while having an identification that is not reliable or easily falsifiable can lead to significant problems for its holders. Countries have been tackling the challenge of identification in different ways, and what international experience shows is that thinking long-term, creating a secure experience, and developing truly valuable use cases are essential points to drive the use of the identification system.

Both decentralized technologies and data sharing through regulated ecosystems, such as Open Finance, can be beneficial in terms of identification. It is quite likely that in the future, we will see more efficient onboarding processes not only in financial institutions but also in other services outside the financial context. As we move towards a scenario of increasingly widespread data sharing, with other sectors of the economy participating in the ecosystem, it is quite possible that cases like "login with Open Data" will emerge, where from smart wallets, such as Australia's myGovID or Brazil's Conta Gov.BR, or even sovereign identities based on decentralized networks, it will be possible to manage which information each service will have access to. We are moving towards an increasingly interoperable reality, where technologies will become a major platform for economic development. But until then, many challenges and questions need to be answered, for example:

How to create a clear and fair governance model to enable data sharing among different sectors?

What strategies could we adopt to establish sustainable economic arrangements, in the long term, that encourage the participation of all stakeholders?

How can we build trust and interest in society for the use of cross-sector data-sharing technologies?

Digital identity is a great start for the transformation of an economy, and when combined with the application of intelligence to the data generated from these human interactions, we can create even better and more inclusive experiences.

Until the next!

Walter Pereira

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the author, Walter Pereira, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or clients of W Fintechs.

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/IDENTITY_IN_A_DIGITAL_AGE.pdf

https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0040787

https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/what-happens-when-billion-identities-are-digitized