#108: Credit in the gig economy: how fintechs are changing the game for gig workers

W FINTECHS NEWSLETTER #108: 03/06-09/06

👀 Portuguese Version 👉 here

This edition is sponsored by

Iniciador enables Regulated Institutions and Fintechs in Open Finance, with a white-label SaaS technology platform that reduces their technological and regulatory burden:

Real-time Financial Data

Payment Initiation

Issuer Authorization Server (Compliance Phase 3)

We are a Top 5 Payment Initiator (ITP) in Brazil in terms of transaction volume.

💡Bring your company to the W Fintechs Newsletter

Reach a niche audience of founders, investors, and regulators who read an in-depth analysis of the financial innovation market every Monday. Click 👉here

👉 W Fintechs is a newsletter focused on financial innovation. Every Monday, at 8:21 a.m. (Brasília time), you will receive an in-depth analysis in your email.

The next frontier of financial inclusion will be offering credit to those who, even with access to financial services, remain on the margins of the trust system: credit market.

In recent years, various fintechs have been promising in providing a first bank account for many individuals, especially in developing countries.

Digital wallets, for example, included more than 40 million Latin Americans in the financial system during the pandemic. Financial inclusion was not only due to the ease of opening accounts provided by these fintechs but also due to factors such as favorable regulation, which combined technology, simplicity, and security, as well as income transfer programs and financial aid that required a bank account for receiving payments.

Despite significant advances in inclusion, many are still outside the credit market. In other words, financial inclusion is just one step in the process of financial citizenship, but merely guaranteeing a bank account for someone is not enough.

Experiences from other countries show that the implementation of digital payment rails is an important step for financial inclusion. Brazil and India are examples of this.

In Brazil, Pix managed to include millions of people by facilitating real-time payments— it is estimated that more than 70 million Brazilians had their first bank account thanks to the system. Similarly, in India, the UPI (Unified Payments Interface) achieved significant results, although the Indian digital ecosystem is more comprehensive and based on a robust digital identity that allowed the secure identification of billions of Indians (to read more about the Brazilian and Indian experiences in payments and digital identity, links 👉 here and 👉 here).

The challenge of offering other financial products and services, beyond payments, lies in access to and analysis of these users' data.

Making payments allows people to generate data within banking ecosystems. This is a fundamental step for financial citizenship. Combined with an open data ecosystem —infrastructures that allow data sharing between different banking platforms — this can result in significant efficiency gains and financial analyses on a given individual.

Brazil and some Latin American countries have followed a path similar to India. Pix, together with Open Finance, are two platforms that can allow millions of people, previously without access to basic financial products, to finally access them. But we still have many challenges, especially when we talk about gig workers, individuals who do temporary or sporadic work, often through digital platforms like Uber, Rappi, iFood, Doordash, among others.

The gig workers market

The gig economy is composed of digital platforms that connect freelancers to clients to provide short-term services or share the use of a good. Generally, service providers do not have contractual ties with the platforms and are compensated based on the number of services performed, without access to health or social security benefits. In 2018, the gig economy generated $204 billion in gross sales worldwide1.

In Brazil, according to the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipea)2, 1.5 million people worked in the gig economy in the transportation sector at the end of 2021, with 61.2% of them working as app-based drivers or taxi drivers.

IPEA data shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the working hours of motorcycle delivery drivers equaled those of app-based drivers and taxi drivers, despite being shorter before. In 2020, motorcycle delivery drivers reduced their working hours less than app-based drivers and taxi drivers, whose hours decreased significantly.

In terms of remuneration, app-based drivers and taxi drivers earned more per hour than motorcycle delivery drivers, but this difference diminished starting in 2019, with both categories experiencing a drop in average hourly earnings.

The global gig economy market

As demand for delivery services and the shared economy increases, the gig worker market tends to grow even more. Predictions indicate that freelancers could represent half of the workforce in the U.S. within a decade3.

A study published in 2020 by Mastercard predicted that the global size of gig economy transactions would reach $300 billion by 2023, driven by factors such as increasing digitalization rates in developing countries and the rapid adoption of smartphones with increased internet access, expanding the number of freelancers and the evolution of the shared economy.

According to the study, although the growth of the gig economy was expected to remain positive globally, the degree to which this growth could accelerate would vary by region.

The U.S. would remain the leader; however, developing regions would contribute more to the global gig economy. India's share was expected to grow by 115% by 2023, and Brazil was projected to see a 129% growth.

In 2018, transportation platforms paid $61.3 billion to 17.3 million gig workers. While North America holds the largest share of payments, other regions are becoming strategically important. In particular, Asian markets — India and Indonesia — represent about 12% of the global total, with significant growth expected in India and Indonesia. Latin America also shows growth potential, with Brazil alone accounting for over $5 billion in payments to more than 1 million gig workers in 2018.

Globally, trends indicate a growth in the number of gig workers. Consequently, attracting and retaining these workers on platforms will become an increasingly significant challenge for some regions. As a result, these platforms are seeking new ways to stand out from the competition, not only for customers and restaurants but also for delivery drivers .

One strategy to achieve this differentiation is to offer quick access to payment when needed, helping to mitigate the volatility of earnings. Additionally, providing benefits such as insurance, credit, and other perks can be crucial in attracting and retaining gig workers.

Platforms in the gig economy

Currently, in most countries, the transportation sector — which includes deliveries, ride-sharing apps, etc. — is the largest within the gig economy, followed by the asset-sharing sector. According to Mastercard data from 2018, the transportation segment accounted for $61.3 billion in spending in the U.S., while the asset-sharing segment reached $52.7 billion 4.

How did gig economy platforms expand?

Since I started studying this market more deeply in mid-2020, due to a startup I helped found in Brazil — a platform that enabled thousands of businesses to continue selling during the pandemic — one thing I always found interesting was how these platforms created strategies to handle the chicken-and-egg problem.

This dilemma is basically present in every marketplace: you need a user base (customers) to attract service providers (suppliers), but you also need a sufficient number of service providers to attract and retain users.

Gig economy platforms solved this in various ways. Some offered financial incentives to both restaurants and initial consumers, creating a critical mass to ensure initial operations. Others invested heavily in marketing to quickly attract a large number of users, while some focused on strategic partnerships with already established companies to leverage their customer and supplier bases.

In Brazil, two players stood out in delivery: iFood and Rappi. Both have aggressive growth strategies, needing to balance three different fronts perfectly: restaurants, consumers, and delivery drivers . iFood achieved significant success with its growth strategy. While Rappi's proposition is more comprehensive, offering a true super app for users, iFood focused on restaurants and supermarkets.

In the Brazilian market, several players tried to enter, whether foreign or local, but few succeeded like iFood and Rappi. Uber Eats, for example, discontinued its operation in the country, citing iFood's dominance and its exclusivity contracts as important factors for this decision.

Despite this justification, market analysts suggest that other factors contributed to the situation. Uber Eats had less flexibility in negotiations with suppliers and partners. This resulted in more rigid governance, making it difficult to adapt to the Brazilian market. This rigidity was also reflected in its fees, which were the highest in the market at the time, reaching 35% of the order value 5. In other words, for a company that did not offer all the services its competitors did, being perceived as the most expensive option did not help its expansion.

In developing countries, the growth of gig workers also indicates a significant increase in the influence of platforms over delivery drivers, reflecting a classic supply and demand dynamic. Although iFood and Rappi have effectively addressed consumer and restaurant concerns in this value chain, delivery drivers continue to be somewhat neglected, facing high fees and issues related to working conditions.

Thus, in the value chain of these platforms, some parts have been well addressed, but there are still many challenges in terms of delivering benefits to those who are also an essential side of this chain: the delivery driver.

Some platforms have established strategic partnerships with financial institutions and fintechs to offer delivery drivers easy access to credit. Additionally, they are focused on improving the safety of these workers by implementing insurance programs that cover risks during deliveries.

The Brazilian government has also proposed regulation for the gig economy. However, it has been criticized by some in the sector for not including adequate social security provisions for delivery drivers, putting their social protection at risk 6. There are also concerns that excessive taxes may further harm the income of these professionals.

Despite these advances, both from a regulatory standpoint and through initiatives by the platforms themselves, there are still considerable challenges in ensuring that all involved in the value chain are equitably benefited, especially the delivery drivers, who play a significant role in the success of these platforms.

The challenges of credit in the gig economy

The credit market grapples with an issue of information asymmetry. Economist George Akerlof addressed this very well in a paper called "The Market for Lemons," highlighting how the lack of equitable information between buyers and sellers can result in adverse consequences — such as adverse selection that may lead to higher interest rates and greater risk for lenders.

This scenario puts gig workers at a disadvantage when seeking credit, as many are denied due to a lack of banking history or limited history. In other words, gig workers are excluded from formal financial services due to the lack of financial data about their income and transactions. Without this data, banks cannot accurately assess these workers' repayment capacity, leaving them without access to adequate credit.

However, gig platforms can use work and income data to provide financial services to these workers.

How can the data from these platforms help?

Unlike informal work, platform work generates an abundance of data about workers' habits and incomes. Because work is monitored and paid digitally, platforms can provide financial service providers with more detailed information about their workers.

But leveraging platform work data to expand access to credit is not straightforward.

To begin with, platforms collect few data fields — usually only name, date of birth, contact information, driver's license, and criminal background — aiming to keep the onboarding process simple — and their systems were designed for operational management, not for credit assessments.

Gig economy platforms have also not yet realized the value of collecting more data, creating a chicken-and-egg problem where without more data, it is difficult to improve credit assessments, but without demand for better credit assessments, platforms do not see the need to collect more data.

Another barrier is that the work data from any platform likely only reflects part of the worker's work and income. In most countries, workers work on multiple platforms, meaning the true picture of their work and income is spread across platforms. Currently, platforms tend to protect this data, making it difficult for a single player, such as iFood, to offer credit, for example.

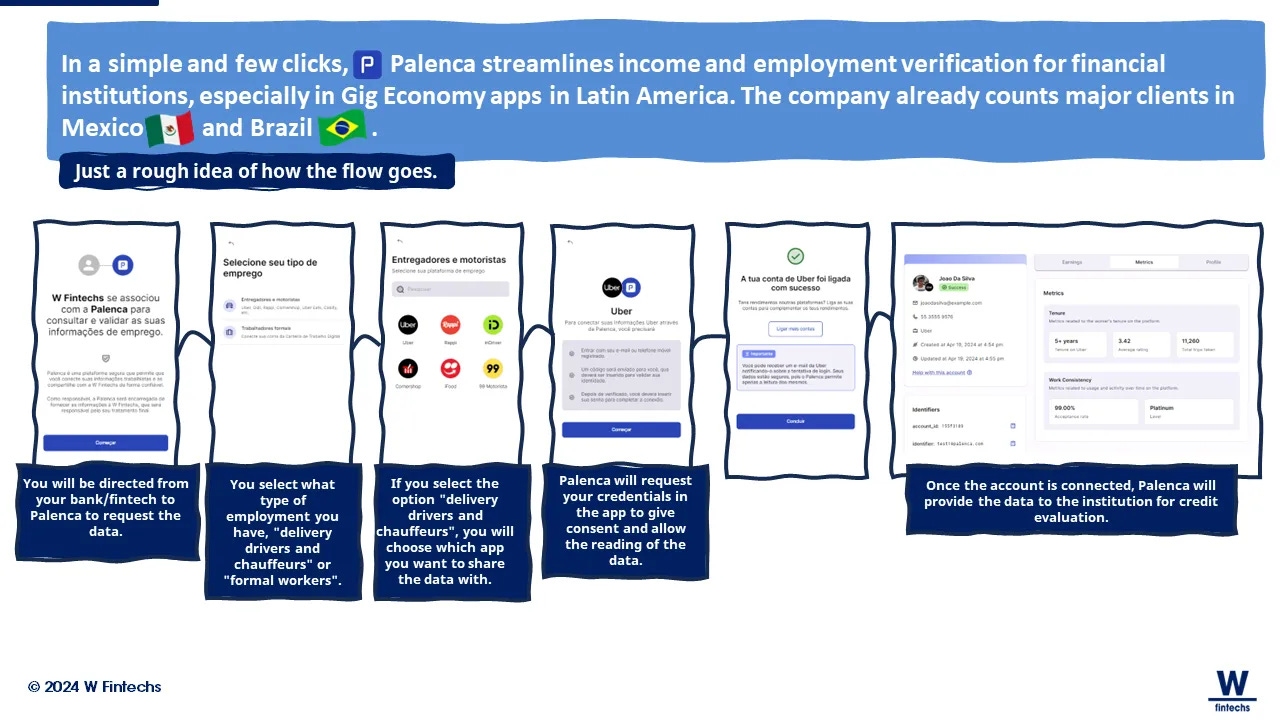

Some startups have found interesting solutions to this, using APIs, where in a few clicks, they can provide financial institutions with a reliable income verification of these workers, with the users' consent (I showed this better in edition 103, link 👉 here).

Still, even when data on gig workers' earnings is comprehensive, it may not be sufficient to reveal the true creditworthiness of the workers. Income volatility, driven by factors such as seasonality and changes in platform prices, can distort the perception of these workers' financial stability.

This volatility does not necessarily reflect the quality or effort of the worker but rather the inherent fluctuations in the digital platform work model.

Additionally, profit data alone can be misleading as they do not fully capture other crucial aspects of the financial situation, such as regular expenses, savings capacity, and debt management. In other words, higher earnings may not always equate to better debt repayment capability.

In these cases, rating data, such as user star ratings, may be more indicative of the worker's quality, but these ratings are often highly compressed, as platforms tend to either remove low-performing workers from the platform or assign them fewer trips.

These limitations further underscore the need to develop more comprehensive credit evaluation methods that take into account the unique nature and volatility of gig workers' incomes.

The Asian and African markets have interesting examples in this regard. In Latin America, which also has a significant number of gig workers, I've spoken with interesting companies as well, but it's still a market with many opportunities to be developed and explored.

An analysis of the Asian and African markets

Despite the challenges faced by gig economy workers, companies like Karmalife and Moove are creating innovative solutions through gig platform data to facilitate access to credit for gig workers, helping them build financial assets such as savings and investments that contribute to their long-term financial stability.

Karmalife

Karmalife, for example, is revolutionizing access to financial services for gig platform workers in India. The startup offers salary advances and a variety of financial products. Its differentiator lies in the use of income data, hours worked, driver ratings, and professional performance metrics to assess workers' repayment capacity and offer personalized loans.

In addition to improving workers' financial liquidity, Karmalife's loans have shown a positive impact on retention, with higher availability rates among those who have taken out loans.

This approach not only facilitated access to credit but also increased the likelihood of repayment since loans are adjusted according to each user's financial capacity and work history.

Typically, when offering credit to these workers, platforms or fintechs need liquidity, usually obtained through financial partners such as banks. However, many of these liquidity providers are risk-averse and reluctant to lend to low-income gig workers, limiting financial services or offering loans with inaccessible rates. Karmalife managed to overcome this barrier in India by partnering with LenDenClub, an alternative peer-to-peer investment solution.

According to a study conducted by CGAP along with the Indian startup, initial results based on a group of 1,500 eligible gig workers for loans were impressive: personalized loans range from 1 to 6 months, one week after loan eligibility, 93% of workers who took out a loan were available to work, compared to 85% of those who did not 7. This suggests that loans help keep workers more available for work, achieving the desired goal of improving retention.

Six weeks after eligibility, these numbers increased to 95% and 89%, respectively. Additionally, the loan repayment rate is high, with 90% of loans granted to workers with limited financial history being repaid on time. Initial results suggest that longer-term loans improve driver engagement in the weeks immediately following loan acquisition.

Karmalife's experience shows that access to advance salary can lead to increased engagement, productivity, and driver retention.

The Indian startup's experience showed that access to advance salary can lead to increased engagement, productivity, and driver retention. Similarly, higher earnings, more hours worked, and higher driver ratings are associated with a lower repayment risk.

Karmalife's co-founder, Badal Malick, highlighted in an interview that using gig platform data as the primary source allowed significantly greater inclusion compared to traditional credit scoring-based models. Additionally, deducting repayments directly from the source, with user consent, simplified the payment process 8.

Moove

Moove, a mobility fintech born in Africa and launched in Nigeria, has also been exploring financial opportunities for gig workers. The startup has developed a proprietary methodology for data collection, credit scoring, and risk management to assist drivers in acquiring an asset essential for their work: vehicles.

Moove has partnered with transport and mobility platforms such as Uber, Glovo, and Careem to identify drivers who meet pre-established performance criteria such as completed trips, ratings, and cancellation rates, similar to those designed by Karmalife.

With the assessment process completed and approved, drivers receive a brand-new vehicle, purchased by Moove itself. Like Karmalife, Moove deducts repayments at the source directly from the platform, recovering the loan over two to four years.

During this period, Moove tracks and analyzes platform work data to set revenue and trip goals for drivers, helping them meet their repayment obligations while maintaining a decent net income. These goals also add value to platform partners as they enable better achievement of their revenue goals and ensure driver availability.

Moove goes beyond what most credit providers do by collecting data on driver behavior through remote sensors, allowing the company to observe driver behavior such as speed or brake usage, geographic distances traveled, and other variables. To achieve this, the startup has developed its own algorithms that enable the use of this data to predict repayment risk.

Moove's product also includes vehicle insurance, health and life insurance, repairs, services, and maintenance. This ensures that vehicles remain on the road, drivers continue to earn, and the asset maintains its value.

LittleApp

LittleApp, a ridesharing platform in Kenya with over 20,000 drivers, has also begun integrating insurance services into its platform. Through a partnership with Britam Insurance, the startup provides travel insurance, protecting passengers, their belongings, drivers, and vehicles during service.

This product has been well received, with over 100,000 policies issued quickly, leading LittleApp and Britam to expand their partnership. Along with CGAP, they launched Imarika Wallet, a savings wallet with a minimum deposit of 200 KSH, 5% interest (averaging 13% in practice), and life insurance coverage of 50,000 KSH, catering to the needs of drivers.

Despite the high expectations the startup had for the product launch, it encountered resistance in the market. During the first few weeks, fewer than 20 drivers signed up, even with marketing efforts focused on benefits such as insurance, high returns, and access to the stock market. The LittleApp team reorganized the product to make it more understandable and offered more incentives for registration, but the response was still limited. The company then adopted an in-person sales strategy, which resulted in 173 new accounts, indicating that more detailed explanations, a more human touch, and direct support were essential for the service's success.

An analysis of the Latin American market

Since the beginning of May, I've been having interesting conversations with fintech entrepreneurs from the gig economy. I found some similarities with the Asian and African markets in two ways: (i) financial access is limited for gig workers, and gig platforms have started to explore this front more after pressures from governments and gig workers themselves; (ii) partnerships with financial institutions or fintechs are crucial for the success of solutions, going it alone can be costly and make the solution unfeasible.

In Latin America, the gig economy has been growing significantly, especially in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

In Colombia, the increase in motorcycle use is transforming the country's transportation, with 74% of new vehicle sales being motorcycles. However, this growth is also associated with an increase in mortality due to traffic accidents. Additionally, the lack of mandatory insurance for traffic accidents poses significant risks to gig economy workers, with an alarming number reporting work-related accidents and illnesses, as shown by a study from Fairwork, an organization dedicated to assessing and promoting better working conditions in the digital economy.

In Colombia, Rappi workers have mobilized against unfair labor practices, such as fluctuating payment rates and arbitrary exclusion of platform workers 9. With most of these workers relying exclusively on Rappi for their livelihood — about 81% claim that their only source of income is working for Rappi — the lack of legal coverage in terms of safety and health has been a concern for the government.

In Mexico, there are some initiatives to formalize and protect gig economy workers, such as the law that allows domestic workers to access social security 10. Meanwhile, startups like Nippy are exploring new business models, offering rest spaces for gig workers in exchange for their personal data. What I found interesting is that the startup's goal is to better understand the behavior of these users, which in the future (a personal hypothesis) could create a broad database for the personalization of financial services.

Trampay

In March of this year, I met one of the founders of Trampay, a fintech that offers salary advances for gig workers, at an event I attended on the impact of fintechs on financial inclusion in São Paulo. Tiago Ribeiro, COO of the fintech, explained how the gig worker market was growing and how the solution they created was helping to ensure more financial dignity for this segment.

Basically, Trampay does a similar job to the Indian startup, Karmalife. The startup emerged from the life experience of CEO Jorge Júnior, whose father was a runner. Initially, they were a benefits platform for workers, who, through a monthly subscription, had access to healthcare, education, and entertainment at a price the worker could afford.

Currently, Trampay focuses on being a complete bank for Brazil's self-employed, offering receivables advances, but with the goal of becoming a complete financial ecosystem. Additionally, Trampay has support points spread across the country, offering storage, parking, refrigeration, among other benefits.

What I found most interesting in Trampay's story were two things: (i) the personal history of the founders, who managed to understand the difficulties that the segment faces; and (ii) when I asked who they were inspired by, they mentioned the Grameen Bank and its founder, Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Prize winner who, through microcredit, changed the lives of millions of people in Bangladesh.

The request for receivable advancement can happen for various reasons, whether it's to recharge a phone, pay an unexpected bill, or even make emergency purchases at the market. To advance the salary, the user has to pay a one-time fee of R$ 6.99 per request (aproximadetely USD 1).

In 2023, the startup raised ~USD 900 million through an FDIC (Credit Rights Investment Fund, which allows raising funds to acquire credit rights, such as future receivables), and in March 2024, it raised an additional ~USD 350 thousands. In 2023 alone, the fintech moved approximately USD 40 million, of which USD 7 million were in advance receivables for delivery workers.

In Latin America, some fintechs have already tried to become banks for gig workers. For example, Plific, a fintech founded in Brazil in 2021, aimed to offer credit to delivery workers based on the analysis of gig platform data (iFood, Rappi, etc). The founders of Palenca also mentioned that they previously attempted to offer credit to this segment, but due to the information asymmetry that existed, they ended up creating an API connector that facilitates banks and fintechs' access to these gig workers' data.

I believe Trampay's main differential is the partnership they establish with companies before granting credit. It may be challenging to increase credit amounts for these workers, but as users begin to use the fintech platform more for payments and receipts, there are possibilities to overcome this challenge. The use of alternative data could also be advantageous for creating a personalized credit score for this segment.

One of the things I believe could be more challenging for Trampay's credit growth is related to the price elasticity of the single fee they charge for receivable advances, due to the variable nature of gig workers' income and expenses. The challenge will be to balance the fee amount with the added benefits they expect to build in the platform ecosystem.

OneCar Now!

OneCar Now! follows a similar approach to the African company, Moove. As a car rental company in Mexico, they offer a range of services to meet drivers' needs.

Additionally, OneCar Now! offers benefits such as exchanging the car for a new one every 3 years, weekly payments, included maintenance, comprehensive car insurance, and even the option to purchase the vehicle for interested customers.

Customers can make reservations online or in person, providing the necessary documents and choosing how they want to pay.

After picking up the vehicle and signing the contract, they can use it according to the agreed conditions, returning it to the specified location and date. The startup has been using data from gig platforms to have more important information in the user analysis and verification process.

Kovi

Kovi, which is one of the largest platform vehicle rental companies in Mexico, has also been doing similar work with OneCar Now!. In a scenario where financing for gig workers is challenging due to the lack of traditional guarantees, Kovi has managed to fill this gap by offering personalized solutions, including weekly income, affordable payments, specialized insurance, and other benefits.

For drivers to access these rental benefits, Kovi has established specific criteria, such as minimum age, experience in mobility platforms, and proper documentation. The company has partnered with Palenca to obtain this data.

By integrating this data into their decision-making processes, Kovi has reduced risks and facilitated car rental operations for gig economy workers.

Looking into the future

While we have included millions of people through instant payment systems, the next financial challenge will be to bring millions of new banked individuals into the trust system: the credit market. This becomes more evident when we look at gig workers, who without formal employment, have a high income volatility, which implies invisibility in this credit market.

In recent years, gig economy platforms have grown significantly in developing countries due to a low supply of formal employment. Although they have worked very well for two parts of their value chain — restaurants and consumers — delivery drivers and drivers have not gained many benefits.

Partnerships with financial institutions can help provide credit to this audience. What I observed studying this market over the past few months is that the model generally occurs in three ways: (i) direct partnerships between gig platforms and fintechs, which may imply that the gig platform does not have a holistic view of users' finances, as many work on more than one platform; (ii) fintechs/banks using APIs that bring data from these platforms; and (iii) fintechs using financial institutions for credit granting and partnering with platforms or API companies that bring this data.

Currently, the financial services available to gig workers are limited. One of the factors is due to the low revenue generated by these services, but as some studies have shown, especially in Africa and Asia, there are indications that the financial services offered by platforms can increase worker participation and retention 11.

The data generated by these platforms is often being used to improve credit analysis. For example, when analyzing a candidate's data, the company can evaluate their identity, financial history, and performance on other gig economy platforms. This information provides a clearer view of the potential client, allowing the company to make more informed decisions about credit approval.

In practice, if a candidate has a rating below 3, a pending debt of USD 350, an acceptance rate of rides of only 0.70 (meaning they accept 7 out of 10 trips), and a history of late payments, the fintech/financial institution could decide that they are not the ideal candidate for credit approval or hiring.

Although companies like Karmalife, Moove, OneCar Now!, and others are demonstrating that platform data can pave a new path for financial services for gig workers, there are some challenges that need to be overcome, such as the chicken and egg dilemma, where platforms are reluctant to collect more data that could benefit more accurate credit analysis, while the lack of this data prevents the proof of its potential benefit.

Another challenge is the low risk tolerance by platforms and lenders, partly due to the low return that these offerings may bring in the short term. I believe that in the coming years, we may see significant advances in this market, but to ensure the effectiveness of these financial services for gig workers, it will be crucial to have mature digital payment infrastructures and well-established data infrastructures between platforms and financial institutions.

If you know anyone who would like to receive this e-mail or who is fascinated by the possibilities of financial innovation, I’d really appreciate you forwarding this email their way!

Until the next!

Walter Pereira

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the author, Walter Pereira, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or clients of W Fintechs.

https://tecnoblog-net.webpkgcache.com/doc/-/s/tecnoblog.net/especiais/nao-foi-so-o-ifood-que-fez-o-uber-eats-encerrar-delivery-de-comida-no-brasil/

https://institucional.ifood.com.br/entregadores/regulacao-para-entregadores/

https://www.solidaritycenter.org/colombia-gig-economy-workers-wage-country-wide-protest-for-rights/

https://mexicobusiness.news/professional-services/news/future-gig-economy