#166: Short Takes: Analyzing Stablecoin Neobanks in Latin America - the case of Kontigo, a Venezuelan Fintech

W FINTECHS NEWSLETTTER #166

👀 Portuguese Version 👉 here

👉 W Fintechs is a newsletter focused on financial innovation. Every Monday, at 8:21 a.m. (Brasília time), you will receive an in-depth analysis in your email.

Welcome to the Short Takes edition! As the name suggests, unlike deep dives, these editions will explore a variety of topics that might later evolve into full deep-dive editions.

Short Takes is designed for entrepreneurs, investors, and operators looking for quick, actionable insights.

Happy 2026! Thank you for following me throughout 2025. I hope this year will be even better than 2025, and that you and your loved ones have an excellent year, with health and peace.

It is difficult to start 2026 without talking about stablecoins. This was certainly one of the most discussed topics on the internet and among regulators throughout 2025. Everyone was, and still is, trying to understand how to integrate this new instrument into the traditional financial system and what, in fact, changes with this way of carrying out transactions in the real world.

This reminds me of a statement made by the then President of the Central Bank, Roberto Campos Neto, in 2021, during an event held by the Central Bank’s own Financial Innovation Laboratory. At that time, Brazil was facing accelerating inflation. Many bankers, journalists, and opinion leaders criticized Roberto Campos for speaking little about monetary policy and devoting more time to topics such as innovation, especially Pix, Open Finance, and the then so-called CBDC, which would later be renamed Drex.

In response, Campos Neto said during the opening of the event that he was indeed attentive to monetary policy, but that he was also preparing the country for the monetary policy of the future. Stablecoins already existed at that time, but they did not yet occupy the center of the debate as they do today. This phrase, “preparing the country for the monetary policy of the future,” says a lot about the role stablecoins have come to play and about the impacts they may generate on the financial system, especially on the dynamics of monetary issuance, interest rate transmission, and the very sovereignty of national currencies.

But after the end of 2025, what becomes clear from several discussions, even if advanced, is that much of the debate around stablecoins is still driven more by technological enthusiasm than by the real mechanics of liquidity. In many cases, efficiency, cost, and speed are discussed, while the nature of the assets that sustain these promises of stability is ignored.

Several regulatory frameworks are trying to harmonize the intersection between digital assets and the traditional financial system, but many of these initiatives still reproduce exactly the structural risk they claim to mitigate. For example, by allowing stablecoins to be backed by bank deposits subject to fractional reserve regimes, the same liquidity mismatch that has accompanied the banking system for centuries is recreated in the digital environment. As Jeff Alvares clearly showed in this article, instruments promised as equivalents to cash at par cannot be supported by assets that carry credit risk, volatility, and dependence on public guarantees during periods of stress or bank runs. In other words, the promised stability ultimately fails to materialize.

I have written several times about stablecoins in this newsletter. Below, I am sharing some previous editions for those who would like to explore the topic further:

In the last months, however, I have been reflecting even more on the impacts of stablecoins. The idea of this edition is not to go too deep into the topic, especially because I believe the discussion deserves a dedicated deep dive or report, but rather to share some perspectives on how certain players are positioning themselves in this market.

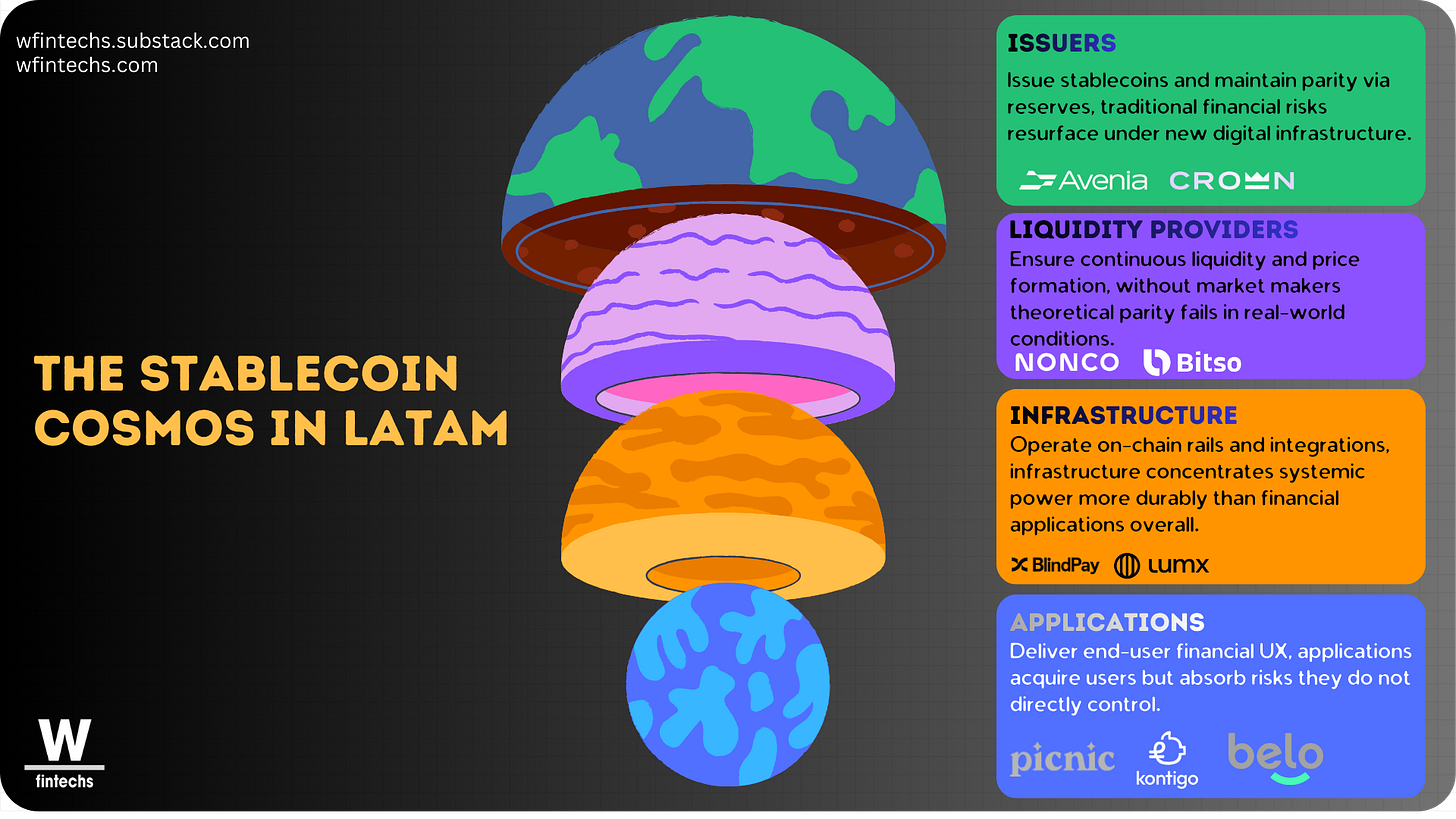

In December 2025, I came across some proposals that I found interesting. A useful way to organize this discussion is to look at the stablecoin ecosystem in Latin America as a stack composed of distinct layers, each with different functions, incentives, and risks.

At the base are the issuers. They are the ones who create the stablecoin and uphold the promise of parity through reserves. This is where the most traditional regulatory debate is concentrated, because it is at this layer that issues such as asset quality, asset segregation, and credit risk arise. In other words, when a stablecoin is backed by bank deposits subject to fractional reserve regimes, for example, it ends up inheriting the same risks as the traditional financial system, but with a new technological wrapper.

Right above are the liquidity providers. These include market makers, exchanges, and trading desks that ensure convertibility, market depth, and price formation. This layer is usually invisible to the end user, but it is where continuous liquidity is preserved.

The third layer is infrastructure. This includes blockchains, on-chain payment systems, bridges, smart accounts, and, more recently, rails that directly connect the crypto world to global card networks and traditional payment systems. It is in this layer that some projects have been concentrating their efforts.

Finally, at the top of the stack, is the application layer. This is where neobanks, wallets, remittance apps, and B2B treasury and payment solutions appear. It is the most exposed layer, because it often tries to deliver an experience that depends on decisions and risks taken at levels it does not directly control. This is the layer I want to focus on today.

Kontigo

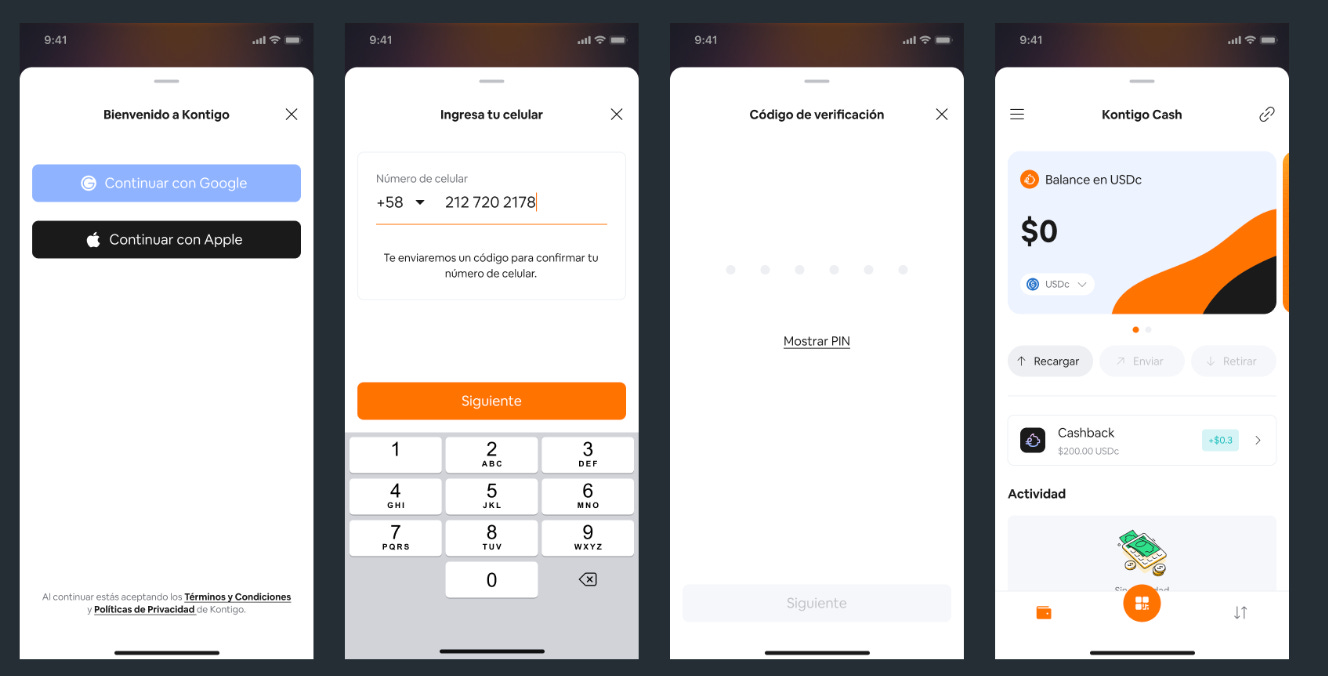

One of the cases I came across in mid-December was Kontigo, a startup of Venezuelan origin, registered in the United States and operating in countries such as Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil. The company offers a useful starting point for understanding the dilemmas and ambitions of so-called stablecoin neobanks, especially in sanctioned countries facing economic and regulatory challenges.

Its proposal is to offer users, especially in countries with fragile currencies and limited access to international financial services, an account based on USDC, issued by Circle, that functions as a stable unit of account, a means of payment, and a gateway to the global financial system.

Kontigo’s value does not lie solely in the stablecoin itself, but in its attempt to package this infrastructure into a simple experience, close to what users already expect from a neobank. The company presents itself as a stablecoin “super app,” combining USDC savings, exposure to cryptoassets such as BTC, local currency payments, and an international card accepted in more than 100 countries.

This narrative, in a way, echoes older promises in the region. In more politicized versions, we have already seen similar proposals coming from the state itself, as in the case of Petro, the virtual currency launched by the Venezuelan government. The difference is that now the narrative is being driven by well-capitalized startups. Kontigo, for example, highlights partnerships with companies such as Circle, Coinbase, and Stripe, in addition to having raised a US$20 million seed round with investors including Y Combinator and Coinbase Ventures.

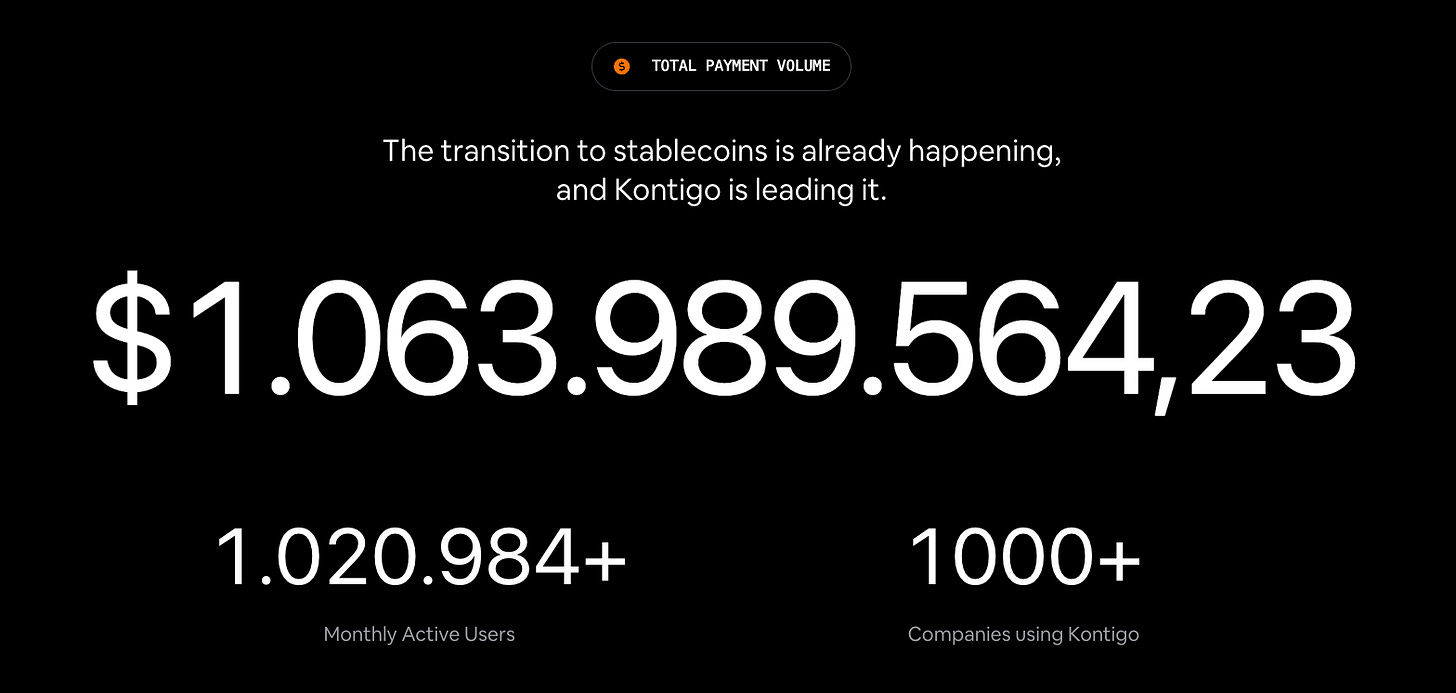

The figures reported by the company (that is, they depend on how it measures users and volume) help convey the scale of this ambition: more than one million monthly active users, over a thousand businesses using the platform, and total payment volume exceeding US$1 billion.

Interestingly, in the same week that the United States arrested Nicolás Maduro, the company experienced an episode of unauthorized access and a temporary suspension of withdrawals. According to the company’s official communications, more than one thousand users were affected, involving approximately USDC 340,000. The company publicly stated that it would process full reimbursement of the impacted amounts, began refunds on a case-by-case basis, and temporarily suspended certain login and withdrawal methods as a security measure. Regardless of any value judgment, the episode illustrates well the risks faced by the layer closest to the end user.

To understand why this type of episode happens, it is worth looking at how the operation was structured. On one side, funds entered through local deposits and transfers at private banks, which served as the gateway for conversion into USDC. On the other, these balances were managed within the application itself, integrated with digital wallets, international cards, and, in some cases, flows that allowed funds to move out of the country via global exchanges.

It is precisely within this complexity that a plausible explanation for the episode emerges. The more intermediaries and connected systems involved in the operation, the greater the number of sensitive points and the higher the likelihood that an issue in one layer will ripple through the others. Kontigo brings together, at the same time, three particularly delicate elements by combining access to dollar-denominated stablecoins, integration with local banks in a sanctioned country, and direct connection to global exchanges within the same operational flow.

Individually, none of these elements is unusual or inherently problematic. The risk emerges when they all operate within the same flow. When local funds can be converted into USDC and quickly transferred out of the country, the platform begins to function, even if indirectly, as a relevant channel for capital outflows. In environments marked by capital controls, this kind of dynamic tends to further strain operational and regulatory boundaries.

Another interesting aspect of Kontigo’s story lies in the institutional context in which it operates. In countries like Venezuela, the line between financial innovation and political maneuvering has always been thin. A report titled Nuevas formas de corrupción y lavado de dinero, published in late 2025 by Transparencia Venezuela, helps illuminate this backdrop by showing how, after the collapse of the Petro and the restructuring of Sunacrip, the country’s former state crypto regulator, the Venezuelan government began to tolerate and, in some cases, legitimize new crypto channels as a way to ease the shortage of dollars and restore a minimal level of functionality to the foreign exchange market.

Within this new arrangement, platforms like Kontigo have come to occupy an ambiguous space. While they provide a real service to individuals and businesses seeking to preserve value, pay suppliers, or access international payment rails, they also end up functioning as a kind of informal release valve for Venezuela’s traditional financial system. This is especially evident when they enable significant USDC top-ups through cash deposits or local transfers, often with limited visibility into the underlying economic origin of those funds. Perhaps this is the most inevitable consequence of operating in an environment where capital controls and informality have gone hand in hand for decades.

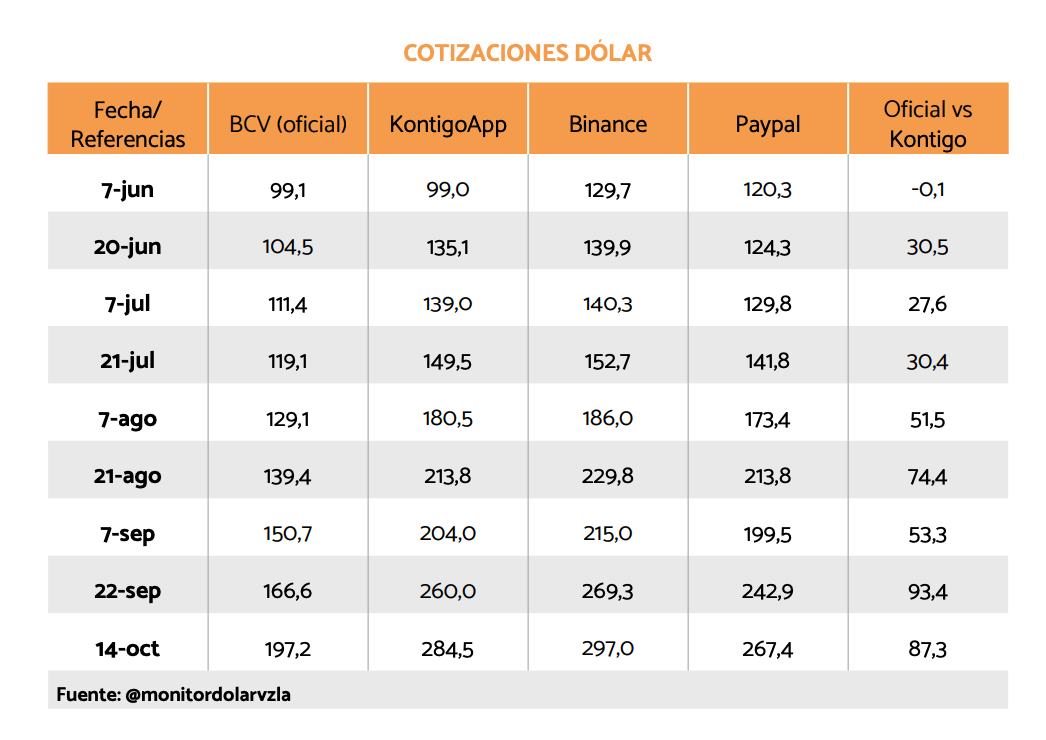

The report itself shows how, from mid-2025 onward, USDC and USDT began to play an important role in shaping dollar pricing in the Venezuelan market.

At times, the exchange rate used by local applications came closer to the parallel dollar than to the official rate. On August 21, 2025, for instance, the spread of the KontigoApp relative to the Venezuelan Central Bank’s dollar reached nearly 50%. From June of that year onward, brokers began offering not only dollars but also USDT and USDC, made available through the two authorized platforms, Crixto in the case of USDT and Kontigo in the case of USDC.

There is also a significant shift in the underlying risk logic. Unlike the Petro period, when control was centralized and explicitly political, the current model distributes responsibilities more broadly across authorized exchanges, private banks, applications, and end users. As the report itself suggests, there is currently no consistent monitoring by banking or regulatory authorities regarding the origin of the funds used to top up stablecoin wallets, nor of the subsequent flows once these assets are transferred to international exchanges.

There is yet another relevant aspect in this case, which is how this model challenges traditional supervisory categories. Kontigo is not a bank, not exactly a global exchange, nor does it operate as a simple non-custodial wallet. It occupies a hybrid space that is difficult to classify, where part of the responsibility lies with local banking partners, part with stablecoin issuers, and part with the application itself. This fragmentation makes any attempt at oversight even more complex and helps explain why, even after the collapse of the Petro, the Venezuelan government ended up tolerating new forms of crypto intermediation, albeit without a clear governance framework.

Gnosis

It is precisely from this observation that the contrast with initiatives such as Gnosis Pay becomes interesting. Gnosis’ focus is not on building a full banking experience for the end user, but rather on addressing, in a more structural way, the settlement mechanics that underpin stablecoin-based payments.

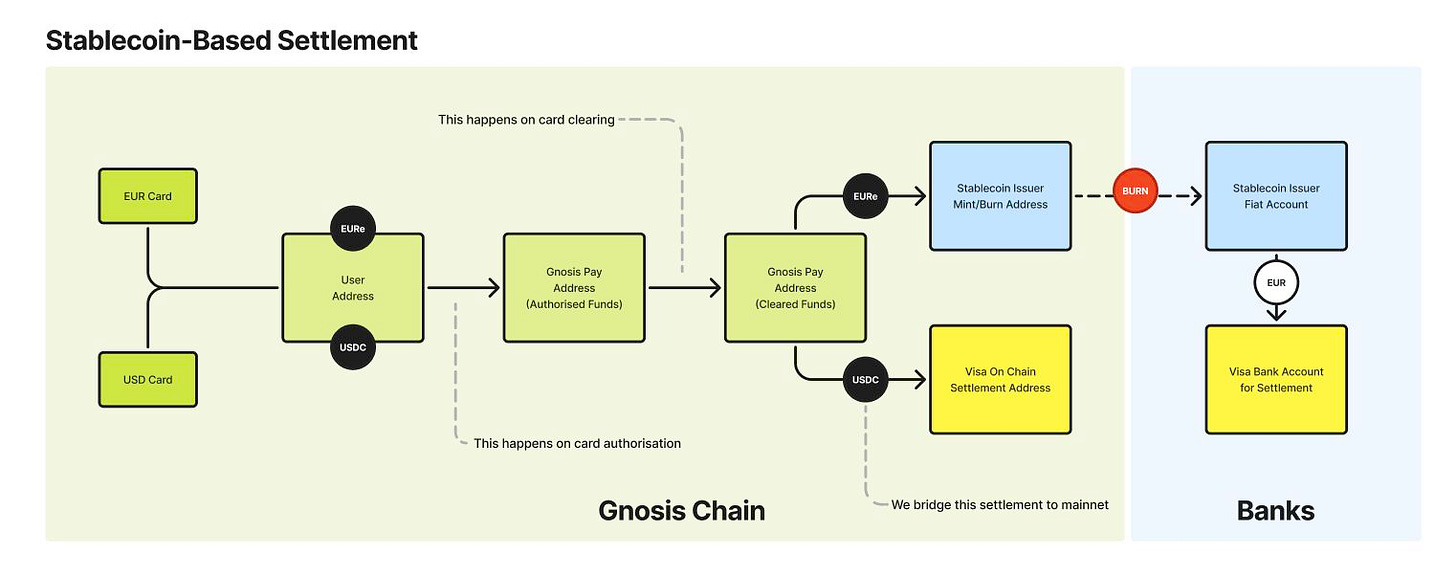

Some materials from Gnosis help make this perspective more tangible. In the model they outline, a card transaction is not first converted into local fiat currency and then reconciled within the traditional banking system. Settlement happens on-chain. USDC moves out of digital accounts controlled by the user and is routed to the addresses that settle transactions with the Visa network, after the standard payment authorization steps. In some cases, this process spans multiple blockchains, but the principle remains the same. Money follows a clear path from start to finish, with explicit rules and the ability to be tracked at every stage of the process.

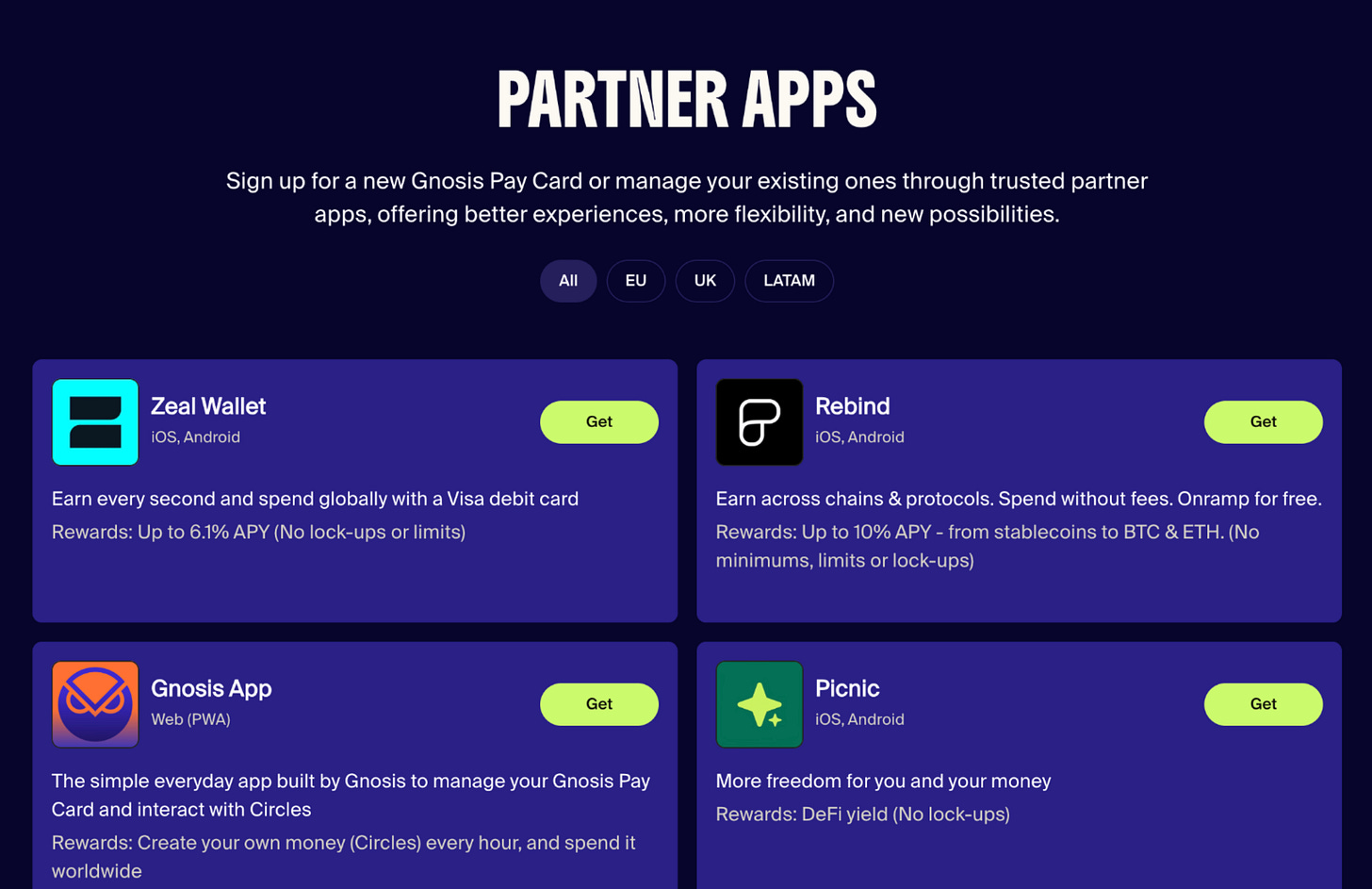

This architecture becomes especially relevant when observing how Gnosis chooses to reach the end user. Instead of operating the interface itself, the company builds a white-label infrastructure layer that allows third parties to launch cards, accounts, and full experiences on top of this rail. This is where partners such as Picnic in Brazil come in, alongside other applications listed such as Zeal, Rebind, and wallets integrated into the Gnosis ecosystem.

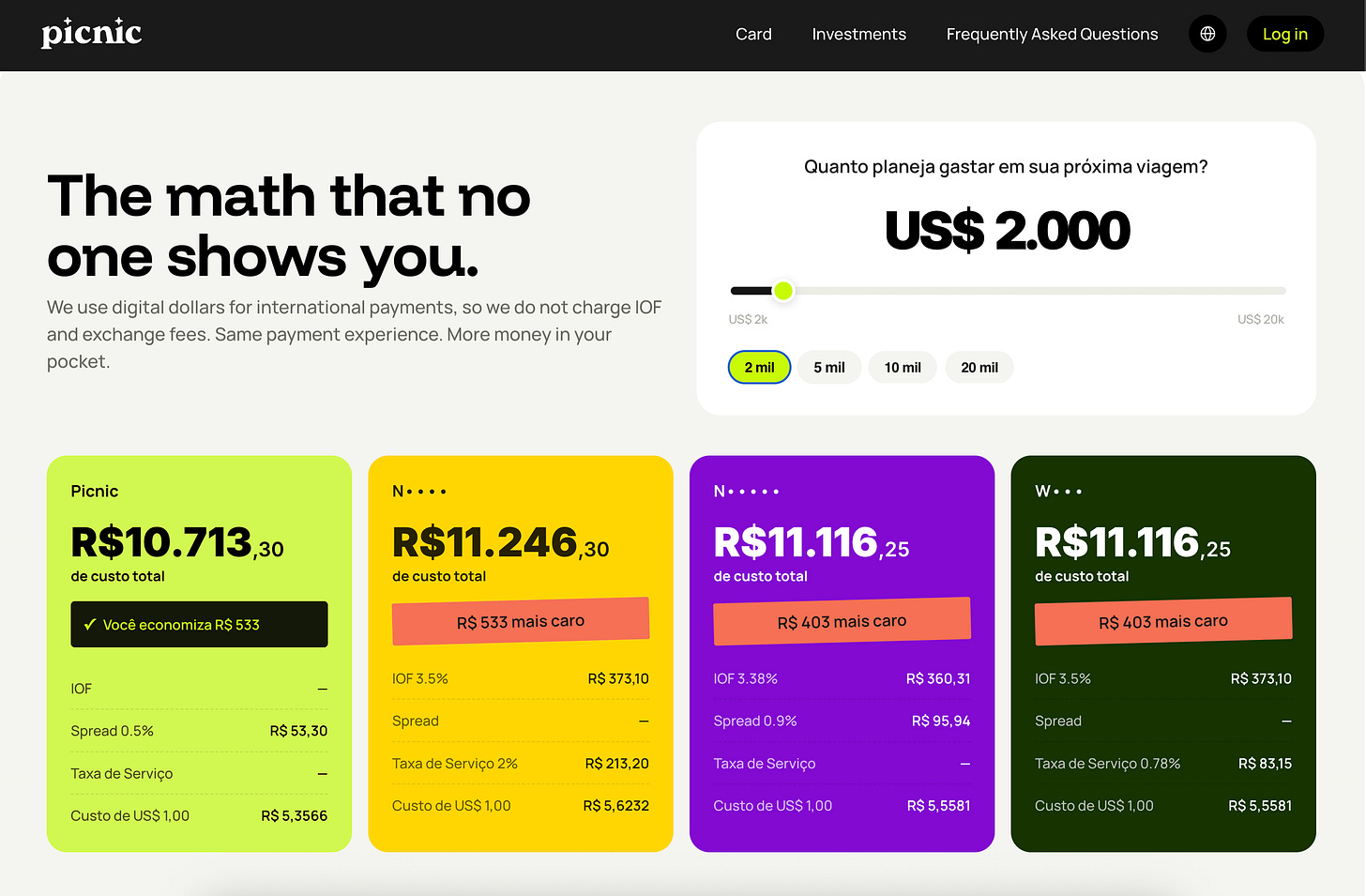

In the case of Picnic, the end user interacts with a product that speaks the local language, promises FX savings, no IOF, and a familiar international card experience. Beneath this interface, however, what supports the model is not a traditional bank account, but Gnosis’ stablecoin-based, on-chain settlement infrastructure.

For 2026

The main lesson already taking shape at the beginning of 2026 is that the boundaries between innovation in digital assets and institutional adaptation remain extremely thin. In sanctioned or semi-isolated environments, crypto structures tend to assume, almost naturally, the role of a functional bridge between local economies and the global financial system. In this sense, Kontigo appears less as an exception and more as a reflection of how well-intentioned startups can end up operating in gray zones simply by responding to a real demand that the formal system has failed to address or has chosen to ignore.

Throughout 2026, we will likely see more players focusing on the final layer, B2B2C, rather than on infrastructure itself. As a result, the maturation of this ecosystem will depend less on the proliferation of new stablecoin neobanks and more on a clearer understanding of the role that each layer can realistically play.

Until the next!

Walter Pereira

If you know anyone who would like to receive this e-mail or who is fascinated by the possibilities of financial innovation, I’d really appreciate you forwarding this email their way!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the author, Walter Pereira, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or clients of W Fintechs.