#FintechFrames: From Mobile Top-Ups to a Neobank in an Emerging Market: How RecargaPay Built a Bank Starting with Essential Payments

W FINTECHS NEWSLETTER #167

👀 Portuguese Version 👉 here

Fintech Frames — Edition #05

Fintech Frames is a series by the W Fintechs Newsletter highlighting the journeys and strategies of fintech companies that have established themselves in the market — whether through an IPO, acquisition, or a valuation exceeding USD 10 billion.

Other editions Fintech Frames

For those looking for stories of founders still in the early stages, 3W in Fintechs dives into the beginnings of many ventures. Click 👉 here to explore all editions.

👉 W Fintechs is a newsletter focused on financial innovation. Every Monday, at 8:21 a.m. (Brasília time), you will receive an in-depth analysis in your email.

In the 2010s, many of the neobanks that today rank among the most valuable companies in the financial sector were born by solving a problem that, seen from today’s perspective, seems elementary, but at the time represented a radical shift in how people related to financial services.

Many of these theses were based on making the banking experience more functional and understandable for the average user, with a strong focus on better customer service. Many of these fintechs started by offering a debit card, a simple digital account, or a better-designed interface, and only later moved into credit, investments, and other financial services.

The ecosystem came as a consequence, and also as a response to the need to increase revenue margins. This movement coincided with a perfect storm in emerging markets, marked by the rapid adoption of smartphones, gradual improvements in connectivity, and a population that began accessing digital services even before fully entering the traditional banking system.

But there is an important detail that is often overlooked when this story is told in a linear way. Not all neobanks followed the classic path of starting as a bank and then becoming a platform. Some were born outside the financial system, solving seemingly peripheral everyday problems such as mobile top-ups, bill payments, or essential services, and only later realized that they were, in practice, building a much more frequent and deeper financial relationship with their users than many digital banks. It is within this group that RecargaPay’s story begins to stand out.

In this edition, I will analyze the thesis behind RecargaPay and how three young Argentinians came together to found one of the largest neobank success stories in Brazil. The reader will quickly notice that Rodrigo, Gustavo, and Álvaro are entrepreneurs by instinct. There is in them an almost natural drive to solve problems. But they became RecargaPay’s founders much more through intuition than by following a predefined playbook. At a time when the market was still in its early stages in terms of smartphone adoption and the attraction of venture capital to Latin America, they bet on the thesis that digitizing processes that cost users time and money, as well as simplifying people’s relationship with financial services, could be the next big wave.

Although most neobanks follow the same playbook, I want to show that, unlike the more common Latin American cases, RecargaPay carved out its own path. The company has raised around US$120 million in investment rounds since its founding and, in recent years, has obtained different licenses from the Central Bank of Brazil to operate in payments and credit.

Entrepreneurs by instinct, founders by intuition

Wasting time in lines, wasting time paying simple bills, wasting time keeping basic services running. For most people, this was always treated as an inevitable part of daily life. For Rodrigo, Gustavo, and Álvaro, this kind of friction was a clear signal of inefficiency.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, entrepreneurship in Argentina meant living with economic instability, recurring crises, capital constraints, and very few references of scalable technology companies in the region. Fnbox itself would be founded in this context, in June 2002, when the concept of a startup as we understand it today did not yet exist, nor was there abundant access to venture capital. It was in this environment that the three began to develop a sharper eye for problems that could be solved with technology.

Rodrigo’s trajectory begins back in the 1990s, when he abandoned the more predictable path of a young economist to dive into the first internet boom. There was no innovation ecosystem, no playbooks, and certainly none of the glamour that many preach today. There was only curiosity, trial and error, and the intuition that software and distribution could change the way people connected and transacted information. This initial impulse was born, in part, from a personal pain point: the high cost of calling from the United States to Argentina, something common for Latin American immigrants at the time.

The experiences Rodrigo had during childhood and youth, especially his education in the United States, laid the foundation for an ambition that would later become clearer: building global businesses, operable remotely and independent of a single country. From the outset, Fnbox operated in a distributed way, with the founder in the U.S., operations in Argentina, and technological development in Ukraine—something far ahead of the norm at the time. This characteristic remains present to this day at RecargaPay.

Álvaro, Rodrigo’s brother, and Gustavo, Álvaro’s college classmate, joined this journey bringing a level of complementarity that went beyond the classic division of roles. From the beginning, Álvaro took on the technology role, sustaining each cycle and pivot of the business. Gustavo, in turn, acted as the operator of it all, responsible for giving economic shape to the group’s ideas.

These individual characteristics led to the creation of Sonico, a social network that would reach more than 55 million users across Latin America. Launched in 2007, Sonico was one of the first social networks designed specifically for the Latin American audience, reaching millions of users in its very first year. It was there that the group learned one of the most important lessons in business, and also one of the most expensive: scaling too early and competing directly with global platforms like Facebook, without solid economic foundations, consumed a great deal of cash and energy.

It was in this context that a conversation emerged with one of the leading investors in the social media ecosystem at the time, Peter Thiel, during a transition period between MySpace and Facebook, when there was still room to compete for attention and social traffic.

The group already held assets that were structurally similar and, more importantly, complementary. Sonico concentrated tens of millions of users and social data such as birthdays, connections, and recurring interactions, in addition to something extremely rare at the time: proprietary distribution via email. In parallel, platforms like Phonico, Tarjetas Telefónicas, and birthday reminder sites (all part of the same group) expanded this base, creating a core of value sustained by recurring traffic and direct relationships with users.

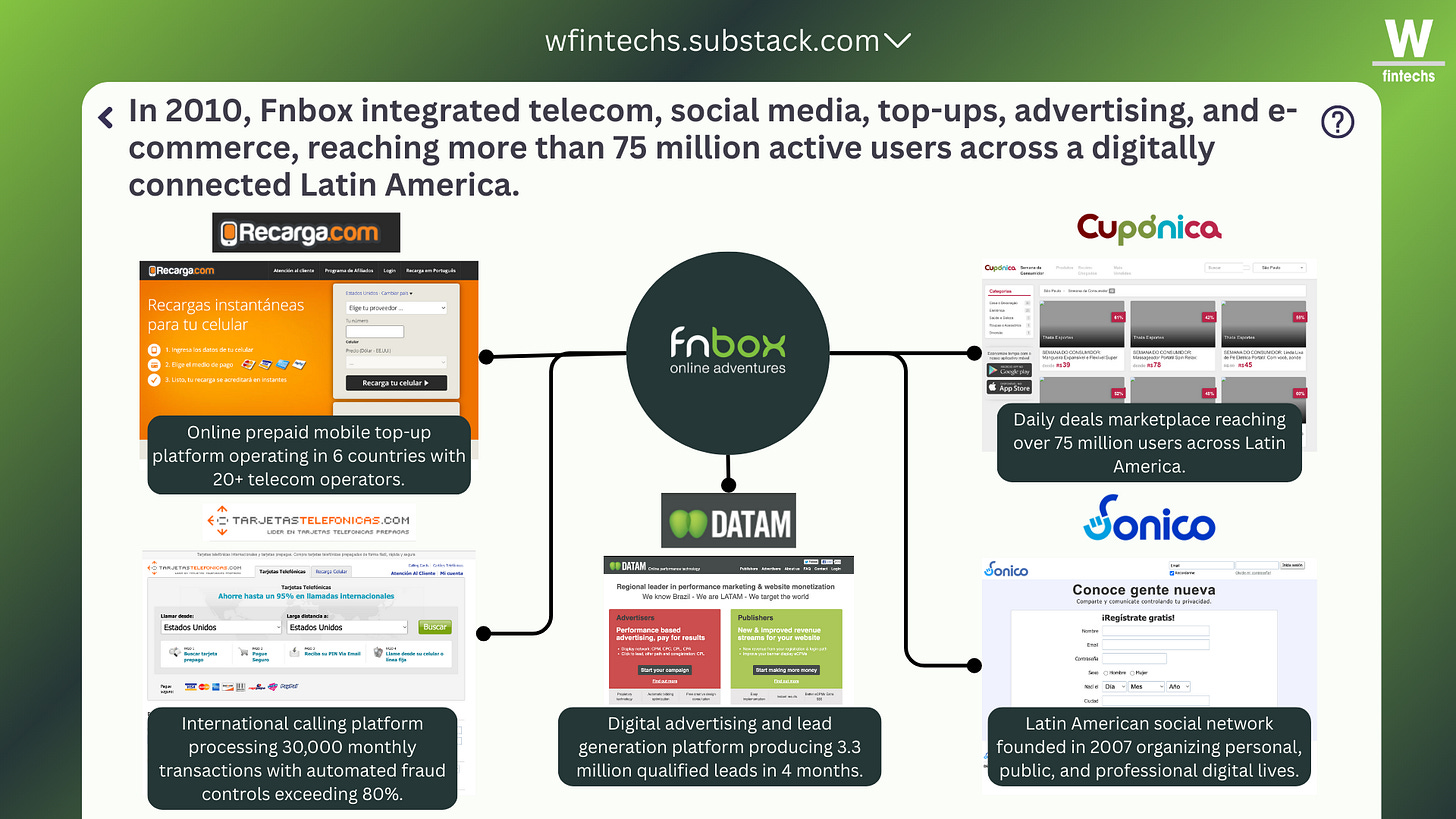

In practice, Fnbox operated businesses simultaneously across telecom, social media, top-ups, digital advertising, and e-commerce, all focused on the Latin American community. By 2010, this set of assets already totaled more than 75 million active users.

Recarga.com allowed users to add credit to prepaid mobile phones in multiple countries, integrating more than 20 operators. Phonico and Tarjetas Telefónicas sold hundreds of millions of international calling minutes.

Cupónica and Datam rounded out the portfolio with daily deals and lead generation. Viewed as a whole, it was a sequence of companies converging around businesses built on proprietary distribution, recurring transactions, and accumulated learnings about people’s digital behavior.

Gustavo himself, in a conversation I had with him in Rio de Janeiro during Rio Innovation Week, acknowledges that one of the main mistakes of that period was scaling the team and infrastructure too early. Added to this was an additional and decisive factor: geopolitical risk. Although the company had regional ambitions, it kept its team concentrated in Argentina at a time of severe institutional instability, marked by a deep crisis, recurring conflicts, road blockades, tensions with the agricultural sector, and constant negative exposure in the international media.

On the other hand, Sonico and other assets within the group created something rare by the standards of the time: a massive user base before monetization. Millions of people interacted daily with the group’s products, ranging from mini-applications to early experiments with recurring digital services, such as mobile top-ups. This base made it possible to test monetization models, advertising, e-commerce, and financial services long before any clear fintech thesis existed. Distribution came before money, and this base functioned as a living laboratory to understand social behaviors, something that would later become a central element in the construction of RecargaPay.

One of these creations was Tarjetas Telefónicas, which already carried many of the elements that would later define RecargaPay. In the early 2000s, international communication was expensive, difficult to access, and dependent on physical channels. The platform sold phone cards and international calling services. Five days after launch, the website was already selling hundreds of dollars in VoIP minutes, quickly validating the thesis. The group explored a clear technological arbitrage between the inflated costs of traditional telecommunications and the efficiency of VoIP, offering much cheaper and simpler calls, especially for Latin communities and immigrants.

The business went on to generate around ten million dollars in revenue as early as 2006, with a significant share coming from recurring transactions. The operation also required the development of proprietary fraud-control systems capable of processing tens of thousands of transactions per month with chargeback rates below the industry average. This led to an insight that would be applied again later: when usage is frequent, predictable, and essential, the transaction stops being an isolated event and starts to sustain an ongoing relationship with the customer.

There is also an irony in this story. The logic that ultimately killed the social network ended up saving it and giving rise to RecargaPay. The concept of unbundling emerged as a direct consequence of these learnings. Fnbox began to function as the structure that organized this multiplicity of fronts built over the years, bringing together social businesses, telecom, top-ups, group buying, and other digital experiments the group had developed by then, all operational and some profitable.

Over time, however, it became clear that one of these fronts was addressing a problem too large to be treated as just another vertical. That was when the group decided to shut down some of its operations across seven countries.

At that point, the hard-earned discipline from the social network phase led the group to focus more heavily on profitable fronts such as top-ups, allowing them to sustain the pivot and build a durable fintech. In other words, if Peter Thiel had come in as an investor, the social network might have had another chance, but there were no guarantees that Sonico would become a global winner, and in that scenario, RecargaPay might never have existed.

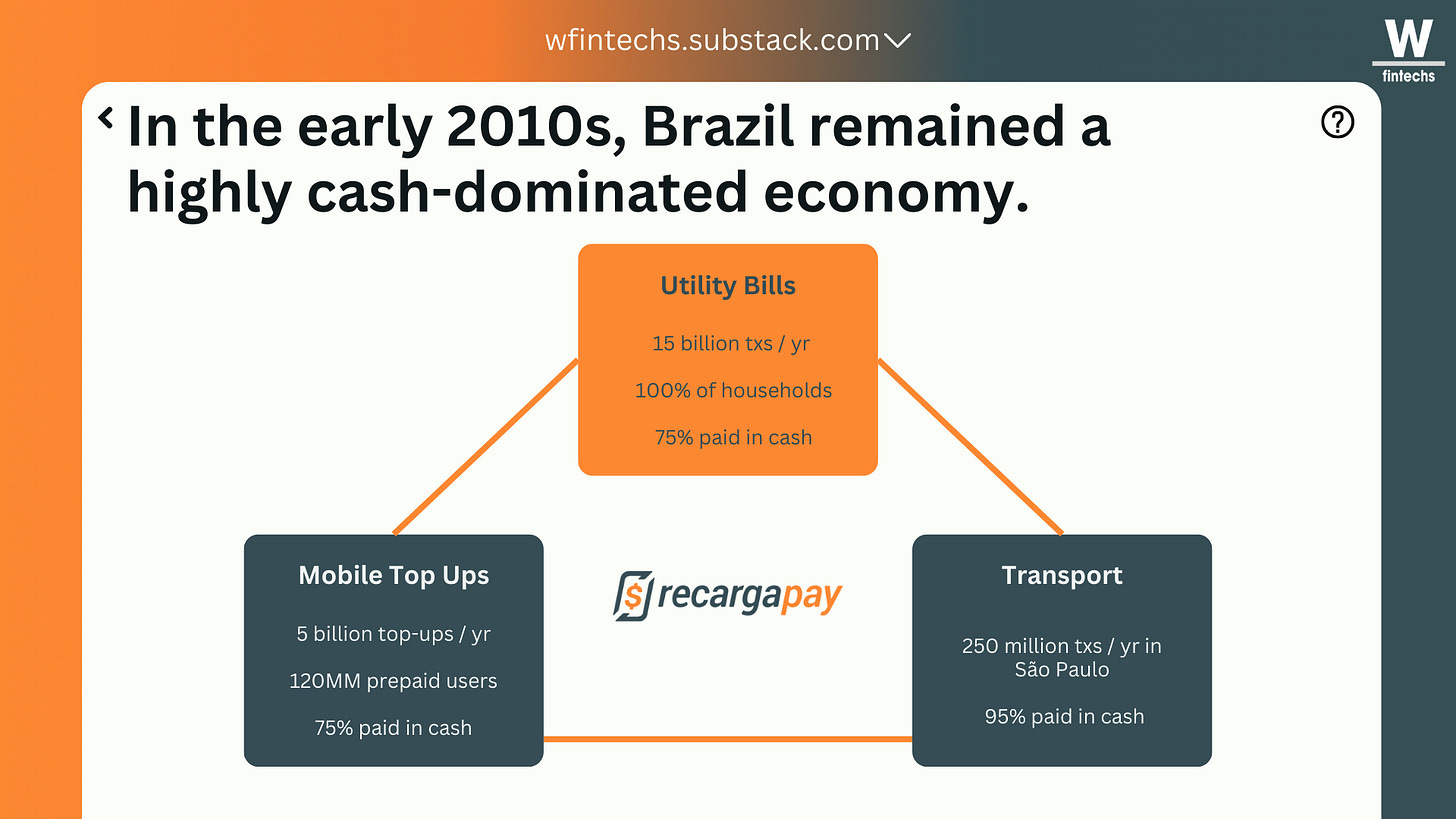

It is within this context that Brazil emerged as a strategic choice. While the United States was already showing signs of saturation in digital services, Brazil combined high technology adoption, a strong prepaid culture, low levels of banking penetration, and an enormous amount of friction in everyday financial life. Physical top-ups, boletos, lines, and cash were part of daily rituals in Brazil. For the founders, this represented an ocean of inefficiencies ready to be digitized.

RecargaPay began to take shape not as a financial product, but as a direct response to a recurring behavior. People had mobile phones, but they lacked time, patience, or seamless access to financial services. They paid bills in lines, topped up credit in fragmented ways, and lived with small, normalized inefficiencies. The thesis was that anything physical, recurring, standardized, and predictable would eventually migrate to digital. If a payment happens every week, every month, for an entire lifetime, it becomes the most powerful possible point of entry.

Fnbox’s definitive shift toward RecargaPay happened because there was a daily relationship between people and money that no one was treating with the importance it deserved. The name change symbolized this transition clearly. It was no longer about top-ups as an isolated product, but about payments as a variable that would perpetuate this relationship. The company was not born trying to replace the bank, but rather by occupying a space the bank had not yet prioritized. Instead of starting with an account or a card, it started with payments for things that were essential to everyday life.

The neobank thesis: why payments are starting points?

For a long time, payments were treated as just another detail in the user journey. Banks viewed them as a cost or as an intermediate step toward a “noble” product, usually credit. More recent fintechs often repeated the same mistake by treating payments as a feature inside a larger app, something that helps with acquisition but does not define the model. What RecargaPay’s trajectory helps illustrate is an inversion of this logic.

When one looks more closely at financial behavior in emerging markets, it becomes clear how costly this shortsightedness has been. Mobile top-ups, bill payments, public transportation, and small recurring payments were always treated as isolated products, each with fragmented experiences, separate channels, and little connectivity between them. This fragmentation created a false sense of simplicity, while in practice it hid a huge amount of friction.

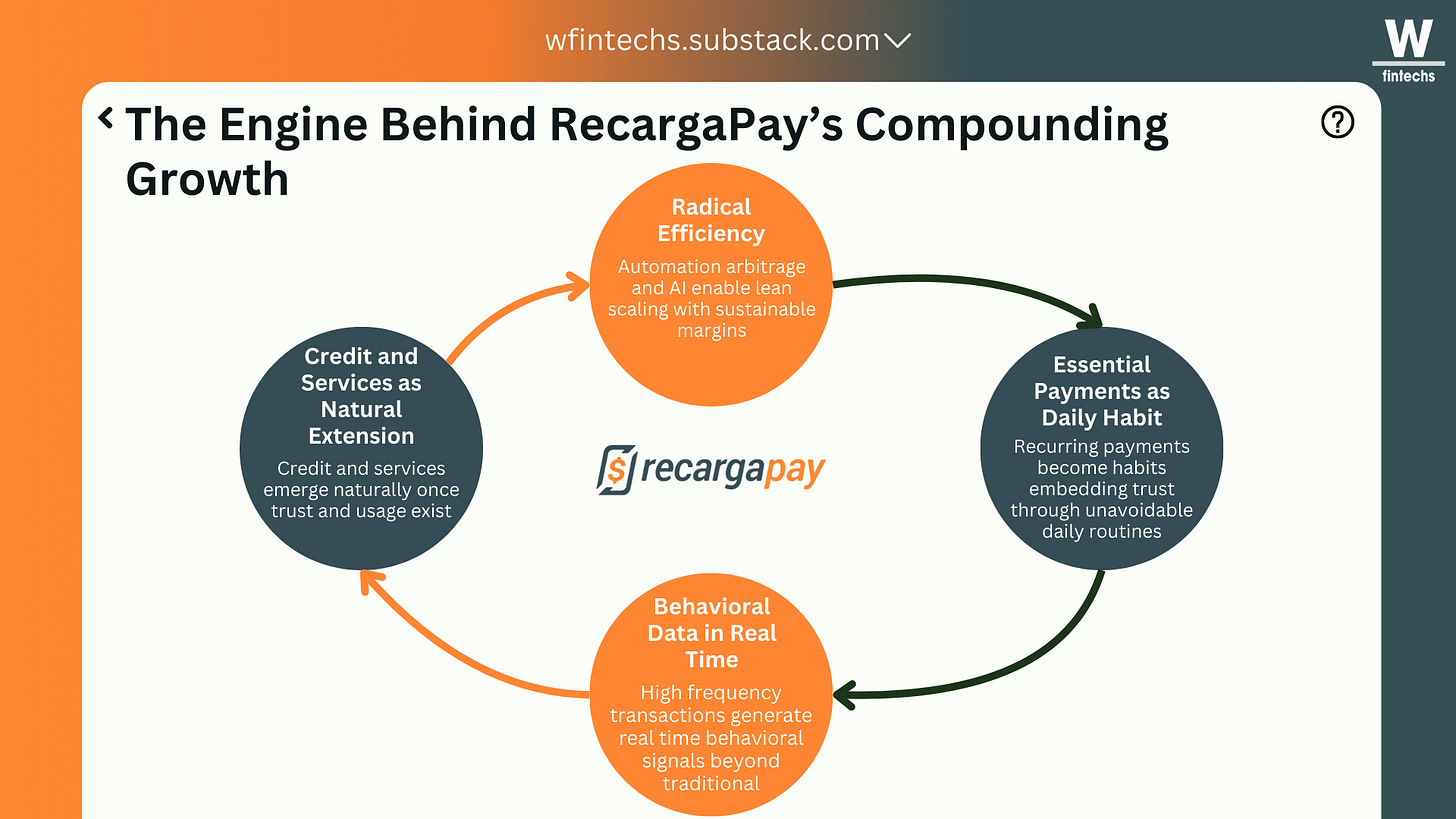

The logic of essential recurring payments changes this perspective because it starts from user behavior, not from the product. It does not matter whether the user is paying an electricity bill, topping up a phone, or validating public transportation. What matters is that the same financial gesture is being repeated with high frequency and low ticket size throughout an adult lifetime. It is through this repetition that habits, trust, and predictability are built. That is precisely why these payments function as a far more powerful entry point into financial life than more complex and sporadic products.

This perspective helps explain why payments precede credit, data, and even financial identity. Before someone takes out a loan, invests, or accesses any more sophisticated product, that person has already paid bills, dealt with money in everyday life, and revealed extremely valuable behavioral patterns.

It is at this point that RecargaPay’s thesis moves away from the traditional neobank narrative and toward something more structural. Instead of starting by offering credit and then trying to generate usage, the company built usage first, on top of unavoidable needs, and allowed everything else to emerge over time. Credit appears as a logical consequence of an already established relationship. This order matters greatly in markets where institutional trust is limited and where formal financial history does not reflect the reality of most of the population.

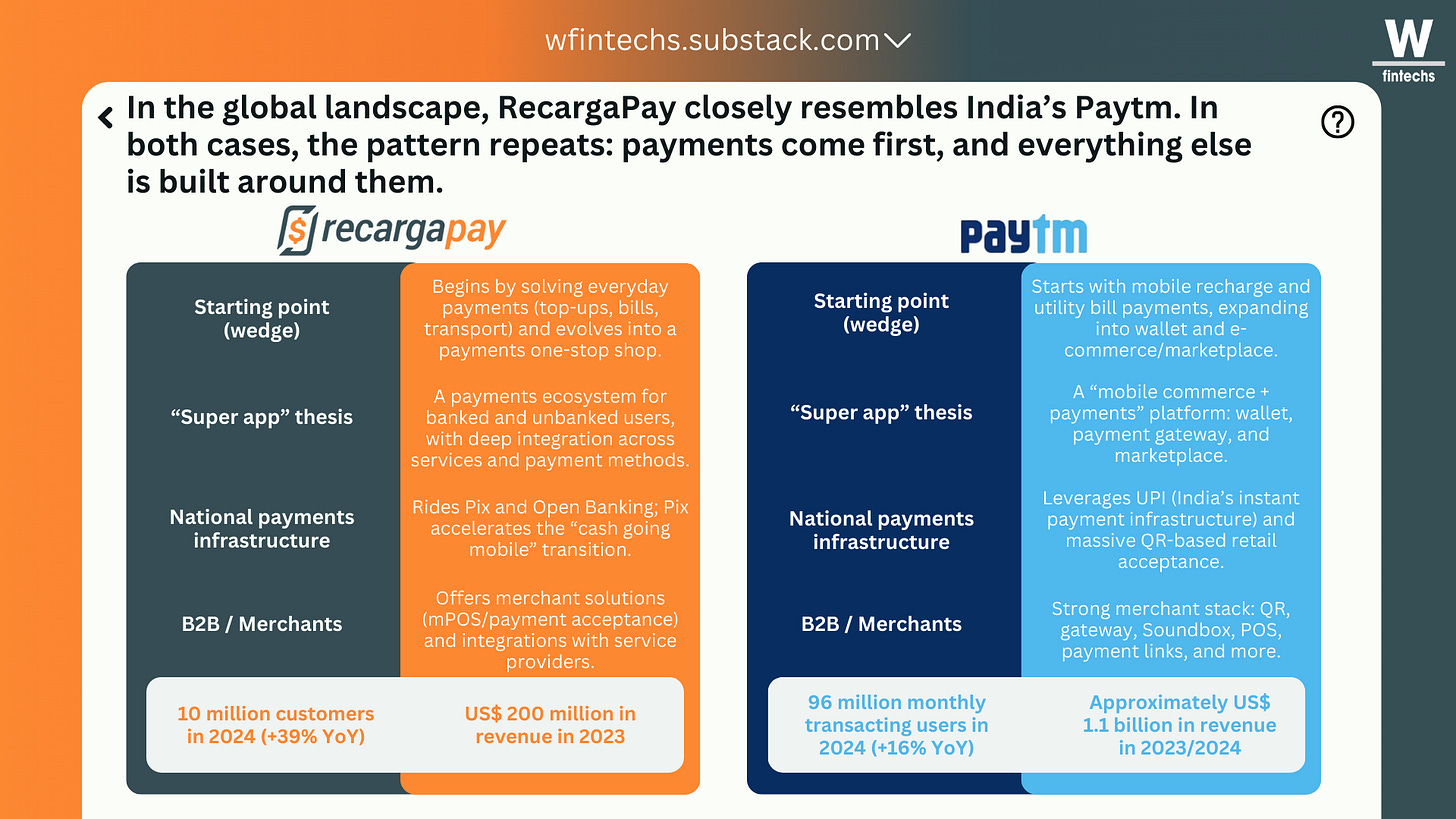

When looking at other global models that followed similar paths, there are several success stories as well. Square, for example, built its model by solving payments for small merchants before expanding into broader financial services. Paytm was born from top-ups and everyday payments in India before becoming a full financial ecosystem. Alipay turned digital payments into a central layer of Chinese economic life long before users ever thought about banking. In all of these cases, the pattern repeats itself. Payments come first, and everything else organizes around them.

The fundamental difference is that, in many of these examples, the narrative came after the practice. They did not initially present themselves as complete platforms, but as simple solutions to specific and recurring problems. Sophistication came over time, driven by the volume of interactions and the density of data generated through everyday use. The same movement can be observed at RecargaPay, which began by solving something considered too small by many traditional players, but which in practice concentrates one of the greatest opportunities for continuous financial relationships.

The perfect storm for building a neobank in emerging countries

Building a neobank in an emerging country requires constant contextual awareness, precisely because in these markets users often enter the digital financial world out of necessity and urgency, not convenience. Brazil is a perfect example of this ambiguity, as it combines continental scale, inequality, informality, and an extremely advanced financial system in terms of payment infrastructure. This combination completely reshapes the order of decisions.

The first variable is the most counterintuitive. A country can have massive smartphone penetration and still carry deep gaps in banking access. Brazil, for example, has 212 million people and around 260 million smartphones, but that does not mean everyone has credit, spending limits, banking relationships, or financial products that make sense in real life.

The second variable is cultural and is often underestimated by those who observe emerging markets from afar. Before the pandemic, cash dominated in Brazil. Analyses of the ecosystem highlighted not only the volume of cash transactions, but also the existence of tens of millions of unbanked people and hundreds of billions of reais in purchasing power circulating outside the traditional banking system. This creates an environment in which everyday friction is normalized, lines are part of the ritual of paying bills, and users learn to switch naturally between channels such as cash, boleto, and cards, depending on what is possible at any given moment.

The pandemic further accelerated the digitization of these services. Emergency Aid distributed more than R$300 billion to over 68 million Brazilians through a digital account. In theory, this should have pushed millions of people definitively into the digital world. In practice, a significant portion of that money flowed back into cash.

It was at this moment that Pix arrived. Recently, in the report “A New Planet Called Pix,” I showed how Pix not only accelerated the digitization of payments, but also reorganized social behaviors.

Read the full report 👇

Link to the full article 👉 here

Within a few months after its launch in November 2020, Pix became a habit for Brazilians and is now present among more than 90% of the adult population, with strong penetration even in classes C, D, and E, where daily usage surpasses that of cards. Data from the Central Bank shows that Pix usage is most intense among young adults aged 18 to 39, but it has also achieved consistent adoption among people over 50, especially for bill payments, family transfers, and top-ups. In the case of mobile top-ups and pay-as-you-go services, Pix reduced friction, removed intermediaries, and brought predictability to those who live on small amounts, allowing balances for essential services to be treated almost as an extension of the money held in an account.

Many fintechs also began using Pix as a settlement rail while attaching personal credit lines, BNPL, and even insurance to the act of paying. RecargaPay is one of these cases. One of the features launched was called “Pix Now, Pay Later,” which allows customers who are eligible for a loan to make a Pix payment now and pay later. Since the beginning of Pix operations in November 2020, the fintech also started offering Pix funded by credit cards to a portion of its customer base, gradually extending the solution to all users.

One year after the creation of the instant payments system, the company saw the number of customers using the technology quadruple. The main use cases were concentrated in bill payments, mobile or transit card top-ups, and peer-to-peer transfers. Cash-in via Pix on the platform, which accounted for 61% in the first three months, represented more than 85% of total user cash-in by 2022.

If you’re enjoying this edition, share it with a friend. It will help spread the message and allow me to keep providing high-quality content for free.

An ecosystem built on top-ups, payments, and credit

The construction of RecargaPay’s ecosystem emerged as a natural response to the company’s growth. When we look at the timeline the company itself describes, it begins with digital businesses outside the “bank,” moves through top-ups, shifts to a full focus on Brazil, and only later incorporates credit, Pix, and the components that now make the app resemble a superapp. In other words, it is clear that the platform was not born trying to be a bank, but rather became a bank as it organized everyday payments.

The first step, and perhaps the most underestimated one, was positioning the wallet as a hub. In emerging markets, a digital account is not just a place to store money, but also a coordination mechanism for recurring needs, because users do not want to navigate multiple banking experiences to solve simple problems. RecargaPay captured this dynamic well by making the app a place to pay, invest, finance, and earn money in a simple and secure way. The digital account with daily yield was another signal of this strategy to be more than just an account.

The second layer is the set of essential payments that generate real transactional frequency. Mobile top-ups are the classic case, but expansion into bill payments, boletos, transportation, and gift cards is what transformed a single-use utility into multiple behaviors. The thesis behind this is built-in frequent payment experiences, where the goal is not for the user to open the app to “check the bank,” but to solve their financial life.

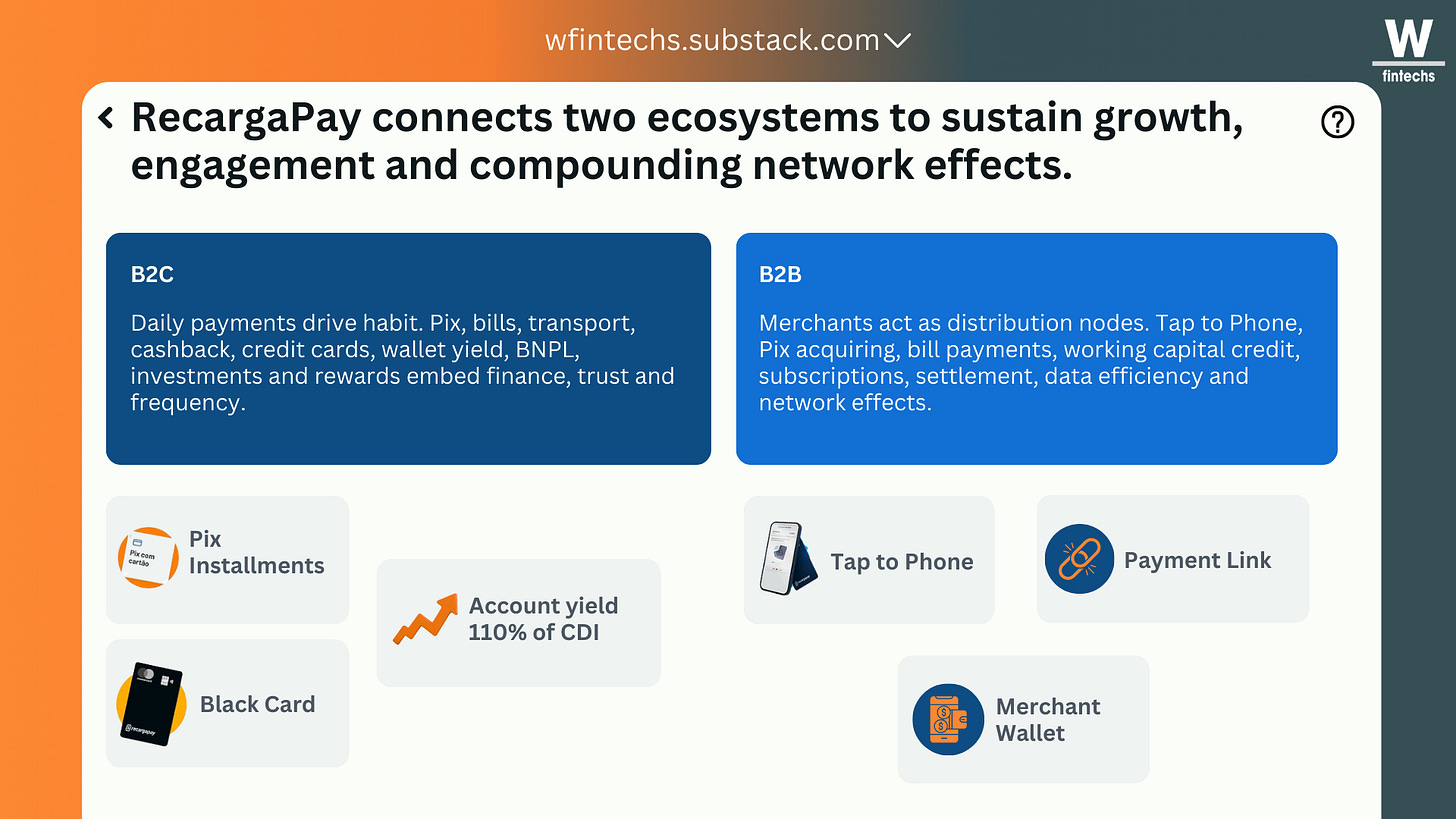

All of this converges into a B2C and B2B2C logic at the same time. RecargaPay starts by solving the consumer’s needs, but gradually also created tools and rails for small businesses, through Tap to Pay, business accounts, and payment links. With each small merchant that begins accepting payments via mobile phone, the ecosystem gains more touchpoints, and consumers find more places where the app makes sense.

In 2024, RecargaPay reached 10 million users and processed R$24.4 billion in total transaction volume. I believe this is where the competitive advantage of an ecosystem lies, precisely in its ability to be indispensable in moments that truly matter. In RecargaPay’s case, what sustains this advantage is not the accumulation of isolated products, but the frequency with which the platform naturally enters the user’s life. Frequency becomes the core of RecargaPay’s thesis because, unlike financial products that are triggered only at specific moments, such as credit or investments, essential payments happen every day and across all economic cycles.

The biggest lesson from recargapay

RecargaPay’s story helps clarify a thesis that is common among some neobanks but still not widely discussed: payments are the first financial language anyone learns. Before understanding interest rates, limits, or even credit scores, every user learns how to pay bills, top up services, and transfer money to solve immediate needs. When a neobank positions itself at this initial point of the journey, it begins to follow financial life as it happens in real time, not only when the user seeks credit.

While researching the company, and through conversations I had with some of RecargaPay’s executives and employees, several lessons became clear, lessons the company has carried across more than two decades of history, from Fnbox to RecargaPay.

The first lesson is that the company was built before the “startup manual” existed, which shaped a culture deeply oriented toward operational efficiency, data, and long-term survival. The business did not begin as a fintech, nor as a promise of financial disruption, but as technological arbitrage in telecom and later as the digitization of recurring transactions. This origin explains why RecargaPay has always treated payments as a continuous relationship rather than an isolated product, and why structural decisions, such as long pivots and shutting down operations, were guided by hard criteria related to cost, margin, and viability.

Over time, this discipline translated into clear competitive advantages. The experience of scaling too early with Sonico taught that traction without sustainability consumes cash and energy. That was when the founders realized that the answer was not to reduce ambition, but to compress it operationally and improve efficiency.

Another important lesson appears in how the company approaches technology and artificial intelligence. AI is present across different areas of RecargaPay’s business, including fraud prevention, risk analysis, customer support, regulatory automation, and internal productivity. The pilot for automating AML analysis during onboarding illustrates this well. In just a few months, the company reduced roughly 90 percent of operational work by automating decisions that previously depended on hours of manual analysis, without inflating teams and while maintaining the necessary regulatory control.

This combination of decisions explains why RecargaPay never pursued growth for growth’s sake. The company learned early on that frequency matters more than occasional volume, and that relationships are built through repeated use of basic but essential functionalities. By prioritizing recurring and essential payments, the company began observing financial behavior in real time. The result is a model that learns from the user before attempting deeper monetization. The main lesson from RecargaPay is that becoming indispensable in a customer’s daily life is the most effective way to scale a business.

If you know anyone who would like to receive this e-mail or who is fascinated by the possibilities of financial innovation, I’d really appreciate you forwarding this email their way!

Until the next!

Walter Pereira

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the author, Walter Pereira, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or clients of W Fintechs.