#FintechFrames: Brex caught Capital One’s attention. What was the journey like, and what are the challenges of this market in the United States?

W FINTECHS NEWSLETTER #168

👀 Portuguese Version 👉 here

Fintech Frames — Edition #06

Fintech Frames is a series by the W Fintechs Newsletter highlighting the journeys and strategies of fintech companies that have established themselves in the market — whether through an IPO, acquisition, or a valuation exceeding USD 10 billion.

Other editions Fintech Frames

For those looking for stories of founders still in the early stages, 3W in Fintechs dives into the beginnings of many ventures. Click 👉 here to explore all editions.

👉 W Fintechs is a newsletter focused on financial innovation. Every Monday, at 8:21 a.m. (Brasília time), you will receive an in-depth analysis in your email.

In the United States, the corporate card market historically developed as an extension of the traditional banking system, and many banks were not prepared for the arrival of technology companies. For decades, the card was treated in isolation from the rest of the financial operation, while startups were operating at a pace that the banking system was not designed to follow.

It was in this gap that the conditions for Brex’s emergence were created. The company’s thesis was to reorganize the way these new companies accessed credit, controlled their spending, and structured their financial lives from the earliest stages of growth.

Contrary to what is often assumed, the problem was not a lack of capital, but the inability of traditional underwriting models to deal with companies that did not yet fit historical risk patterns. Well funded startups were assessed using the same logic applied to small local businesses, creating a structural mismatch between perceived risk and actual risk.

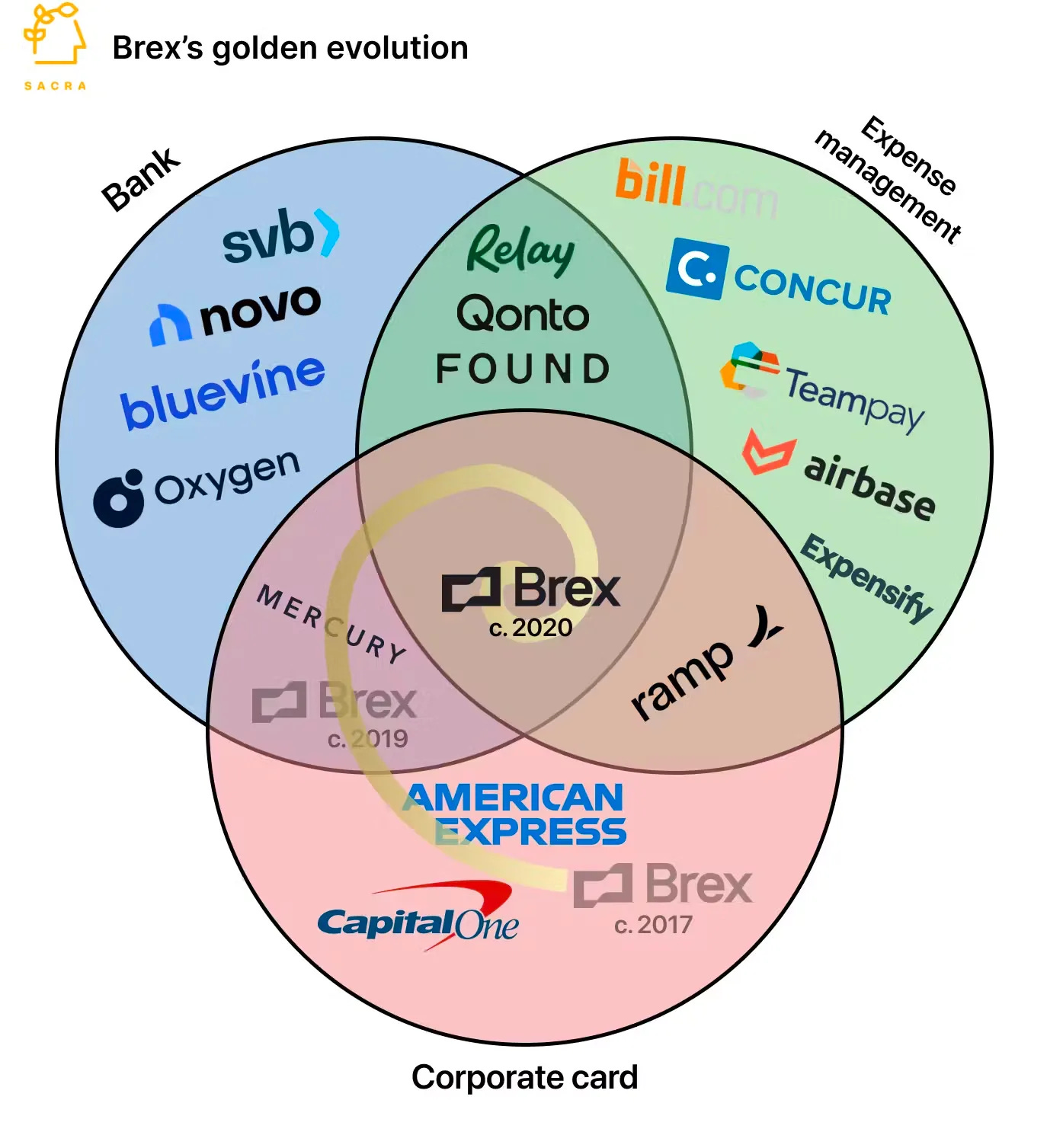

Brex was born focused on payments and grounded in the attempt to build a new layer of financial interpretation for these new companies. The corporate card was the first entry point to access spending flows, payments, and financial decisions that had previously remained fragmented across banks and disconnected systems.

Since its founding in 2017, Brex has gone through a trajectory marked by highs and lows, operating for years with a high level of cash burn. At one point, the company was burning around US$17 million per month and, according to market sources, had enough cash only until March 20261. It was in this context that a series of internal moves emerged, combining cost cuts, including the layoff of nearly one third of the team, with an even stronger focus on increasing operational efficiency. The results of this adjustment began to appear in the first quarter of 2024, when the company managed to reduce cash burn by approximately 90 percent compared to the same period of the previous year.

Over this journey, Brex raised more than US$1.5 billion through primary and secondary rounds since 2017. At the peak of the valuation cycle in 2022, the company was valued at more than US$12.3 billion. In February, the startup projected reaching annual net revenue of US$500 million in 2024 and, just two months later in April, reported growth of more than 154 percent in realized revenue.

This path helps explain Capital One’s interest in Brex and the outcome of a transaction estimated at US$5 billion, representing a return of roughly 700 times over nine years for investors who backed the company from the beginning.

Throughout this edition, I want to show how Henrique and Pedro became inevitable founders, from their early days on Twitter and online forums, and also explore what Brex reveals about the corporate cards and expense management market in the United States, as well as the challenges that emerge when competitors begin to do the same things you do and start competing for the same space within companies’ financial stacks.

The problem traditional banks could not solve

Access to capital has always been one of the main determinants of company survival and growth in the United States, but also one of the most unequal mechanisms within the American financial system. Even companies already backed by institutional funds face recurring difficulties in accessing corporate credit. Startups with US$1 to 2 million in venture capital often received credit limits below US$20,000 from incumbent banks, amounts insufficient to cover basic operating expenses such as software, cloud services, marketing, or corporate travel. In practice, this pushed institutionally funded companies to operate using founders’ personal credit cards.

Some Federal Reserve reports help explain this behavior. Commercial banks tend to restrict credit to small businesses because the cost of evaluation, monitoring, and compliance for smaller operations is high, while risk adjusted profitability is lower than that of large corporations 2. This dynamic ends up reproducing a bias against growing businesses, even when those businesses show solid economic fundamentals.

This bias manifests itself even before a formal rejection. Approximately 40 percent of potential borrowers do not even apply for credit due to the level of bureaucracy involved. At the core of this problem is the inadequacy of the data used for risk assessment. Traditional banks continue to base decisions on retrospective information such as personal credit history, three years of financial statements, and personal guarantees, while startups operate with forward looking structures, volatile revenues, and business models still under construction. This misalignment creates a gap that prevents risk analyses from being compatible with the economic reality of these companies.

The puzzles of Brex

It was in this context that the opportunity for Brex emerged. But the story had started much earlier. Henrique, from São Paulo, and Pedro, from Rio de Janeiro, met in 2012 while debating on Twitter. In a podcast for his brother, Ale Dubugras, Henrique recounts that at the time he had zero hesitation about starting conversations online.

Both were already known at that time for their achievements on the internet. Pedro, at age 13, had been the first person to jailbreak the iPhone 3G in Brazil, something that earned him interviews and a certain reputation as a prodigy. Henrique, at 14, had already created a gaming company that ended up receiving a patent notice from Apple.

The exchange on Twitter eventually turned into a Skype call. Then another. Then another. Until, at some point, those conversations began to converge around a problem both of them were experiencing and that, coincidentally, many other people were facing as well.

At the time, because they played online games and consumed digital products, Henrique and Pedro ran into the problem of paying online. Buying in game accessories, credits, digital items, or online services in Brazil was a poor experience.

Back then, PayPal barely worked in Brazil. Cielo and Redecard, in turn, were designed for physical retail, not for online flows.

That was when the direction of those Skype conversations changed. In this context, the idea for Pagar.me was born. In 2013, they began building what would become known as the Brazilian Stripe. A payment gateway designed to be developer first and with less friction.

Both enjoyed programming, but over time, the division of roles happened naturally. Pedro focused on engineering. Henrique took on sales, relationships, and everything that needed to happen for the business to exist outside of code.

Pagar.me became one of the largest payments players in Brazil, which led to the company being sold to Stone in 2016.

The sale price to Stone was never officially disclosed. Some say they sold control of the company for R$1 million. A small amount, but one that allowed them to enter the Stone ecosystem.

After their first exit, both went on to study at Stanford. There, they tried to build a virtual reality startup. But the timing was not right, and they had little experience in the field. Then they noticed another problem. Startups in Y Combinator were able to raise millions in funding, but could not obtain a corporate credit card. That was when, in 2017, they left Stanford and founded Brex.

The Brex thesis

The Brex thesis was lived by the founders themselves. Even with US$125,000 in cash from Y Combinator, Henrique and Pedro were denied when applying for a corporate credit card, among other examples.

Most institutions continued to assess young companies using parameters designed for mature businesses, with underwriting based on the founders’ personal FICO scores, requirements for personal guarantees, and long manual processes. For newly created startups, often led by foreign founders without a U.S. credit history, this model became exclusionary.

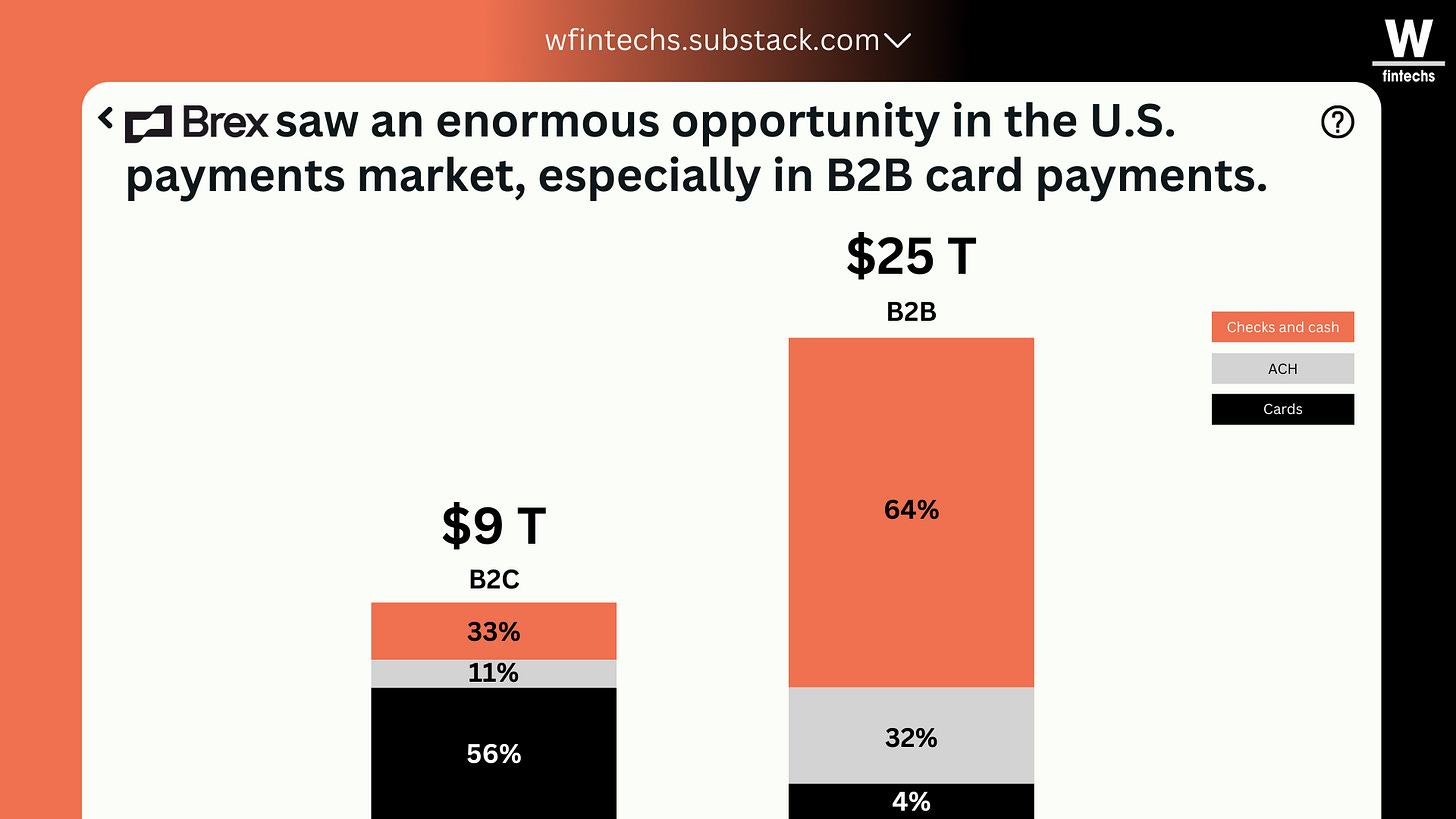

This problem became even more evident when looking at the broader market context. The B2B payments market in the United States moves around US$25 trillion per year, roughly three times the size of B2C, yet only 4 percent of those payments are made via cards. Checks and ACH continue to dominate precisely because of the friction that still exists in access to corporate cards in the country.

Product design and evolution

This was when Brex began to take shape. The question guiding the company’s first steps was not how to compete with banks on traditional products, but how to redesign the very starting point of the financial relationship between a startup and the system.

The corporate card emerged as the most direct interface with day to day spending, especially because many B2B vendors did not accept ACH from early stage startups, making the card a minimum point of operational survival.

Brex’s decision was to invert the logic of risk assessment. While banks analyzed the founders’ personal FICO scores, Brex chose to look at cash on hand, institutional backing, and the company’s spending patterns. The first product was a corporate charge card with mandatory monthly settlement, whose limit was defined primarily by available cash.

This structure reduced risk and, at the same time, allowed limits between ten and twenty times higher than those offered by incumbents such as AmEx, without requiring personal guarantees.

The MVP was a corporate card for startups, without the ambition of solving the entire financial life of the company all at once. The priorities were fast onboarding, high limits, and the absence of personal guarantees. The product was delivered in about four months, with approval processes taking up to 24 hours.

Brex started with only eight pilot customers, many of them foreign founders or companies excluded by the traditional financial system.

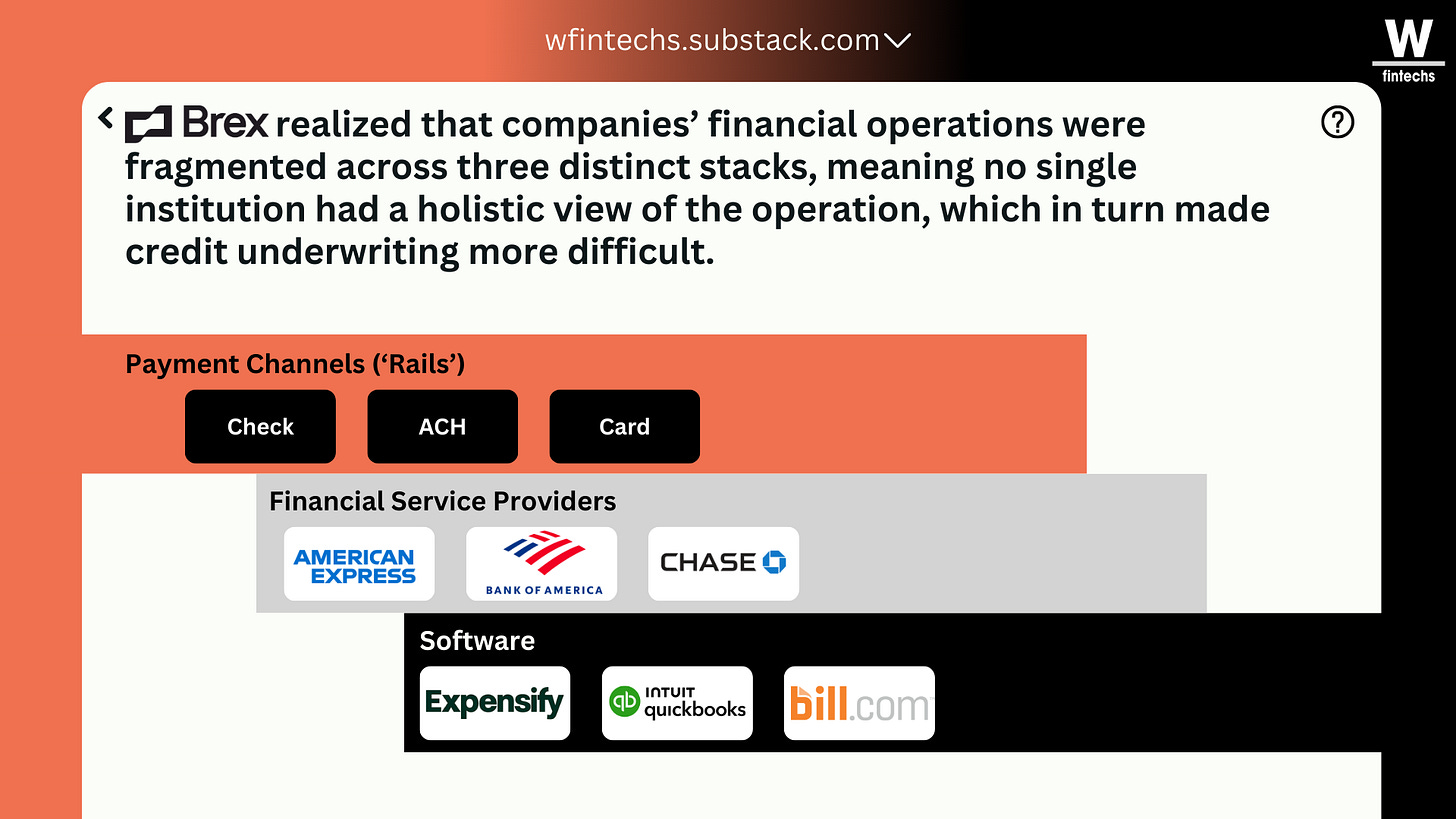

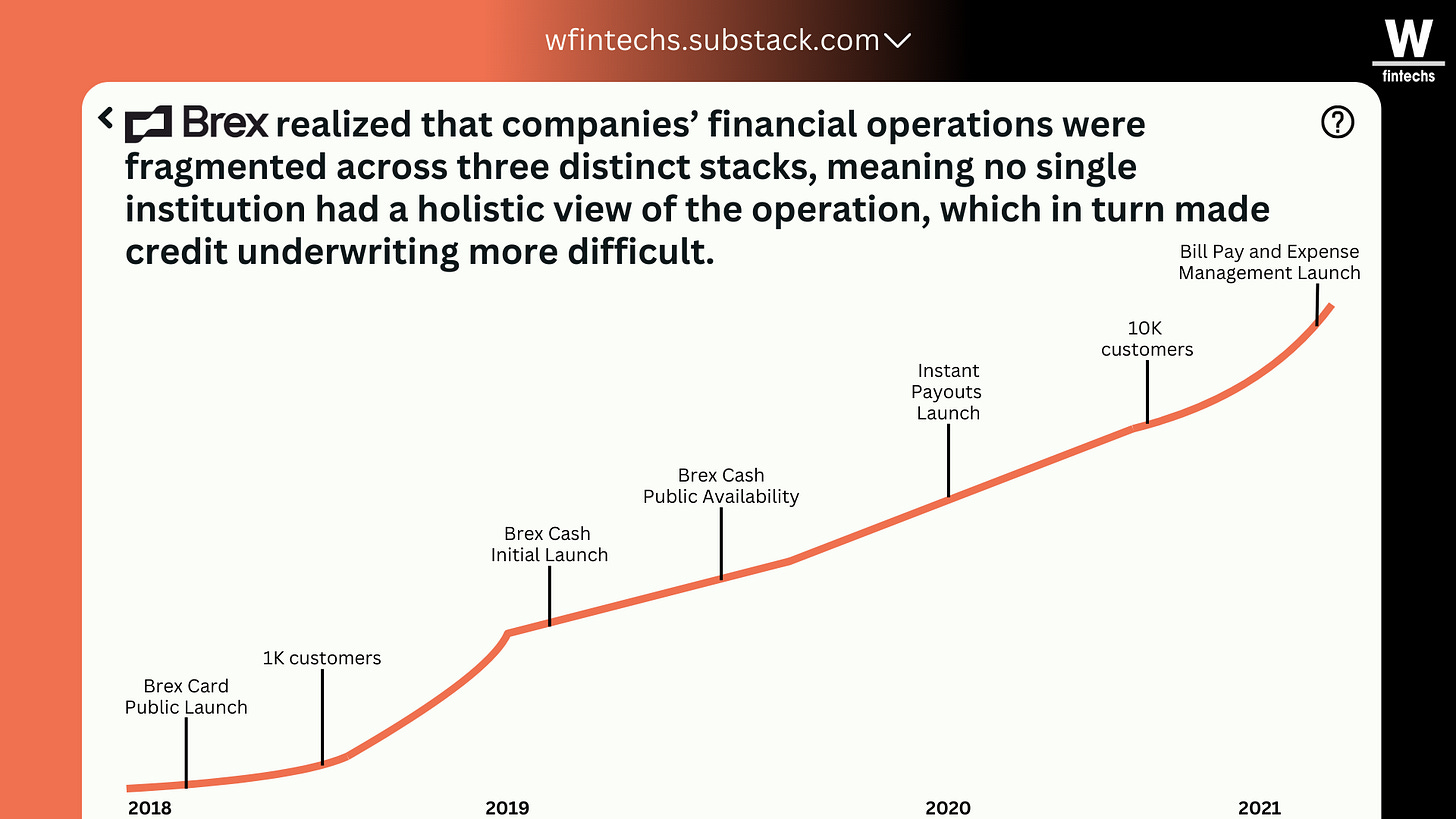

This initial design also revealed a deeper problem in the B2B financial system. Companies’ financial operations were fragmented across three distinct stacks: payment rails, banks, and software, forcing SMBs to operate with six or more different financial providers, with no single institution having a holistic view of the operation.

By using the card as the entry point, Brex positioned itself in a privileged spot within this fragmentation, observing spending flows, behaviors, and operations that traditional banks simply could not see. By treating the corporate card as the starting point, the company built a foundation that explains not only its initial adoption, but also why that simple product would become the first building block of a larger ambition, which would later expand into accounts, financial management, and an integrated platform.

The growth strategy

Another interesting point in Brex’s story was its growth strategy. They did not start by trying to conquer the entire United States. Instead, they focused on winning a radius of just a few miles where a disproportionate share of the market they wanted to attack was concentrated. In an interview with CNN, Pedro explains that within a radius of roughly 10 miles around San Francisco there were around 40 percent of the most relevant technology startups in the country at that time3. In other words, a large share of decision makers and network effects were located there.

This led them to place billboards across the city, mainly because it was the cheapest way to acquire that specific customer. The entire billboard inventory in San Francisco cost something close to US$300,000. For that concentrated audience, customer acquisition cost was orders of magnitude lower than outbound sales or fragmented digital media.

Unlike many fintechs, Brex relied on three growth pillars:

Founder referrals;

Network effects within the venture capital ecosystem;

The use of anchor customers as social proof. For example, when companies such as DoorDash, Zoom, and Coinbase began using the platform, Brex stopped being seen as a new fintech and became significantly more legitimized. Marketing ended up becoming a consequence of the customer portfolio itself.Referências entre fundadores.

The strategic and management pivot

But not everything went according to plan. The first major inflection point in Brex’s growth cycle came at the end of 2023, when the company began to feel the effects of the reversal of the abundant capital environment that had supported the previous fintech boom.

This pressure translated, in early 2024, into a reduction of approximately 20 percent of the workforce, affecting 282 people, in an attempt to reduce cash burn and make the operation more agile and focused on what truly generated value for customers 4. At that time, Pedro wrote:

“With our focus on financial software and high-quality growth, we grew gross profit by 75%+ last year. While we're proud of those accomplishments, we still have a way to go to ensure high-velocity growth and profitability for years to come. Combined, these changes enable us to get there and become cash flow positive with the money we have in the bank.”

At the same time, Brex realized it needed to simplify both its execution and its product design, removing layers of management and bringing leaders closer to day to day execution in order to accelerate decisions and improve the quality of launches, a move that would result in Brex 3.05.

The company reconfigured its execution model, flattened its organizational structure, and abolished fragmented planning processes in favor of a One Roadmap, with greater rigor in choosing what was truly a priority and less tolerance for initiatives disconnected from the customer experience and product cohesion.

This design change resembled a manifesto of focus and choice, in which only themes that represented step function changes in the user experience were kept, while everything else was discarded, and the CEO himself assumed the role of chief editor of what would be shipped.

“We release 4 times a year, and each release has no more than 3 big themes. This forces me to choose what truly matters, allowing us to make a large, company-affecting investment in the few things that are step-function changes to the customer experience, and drop everything else.”

This reorientation was also reflected in the evolution of the product portfolio. Brex initially became known for its corporate cards and cash management accounts for startups, but over the years expanded its scope to include bill pay tools, expense management, accounting automation, travel, and banking and treasury services, seeking to become a more complete business finance platform.

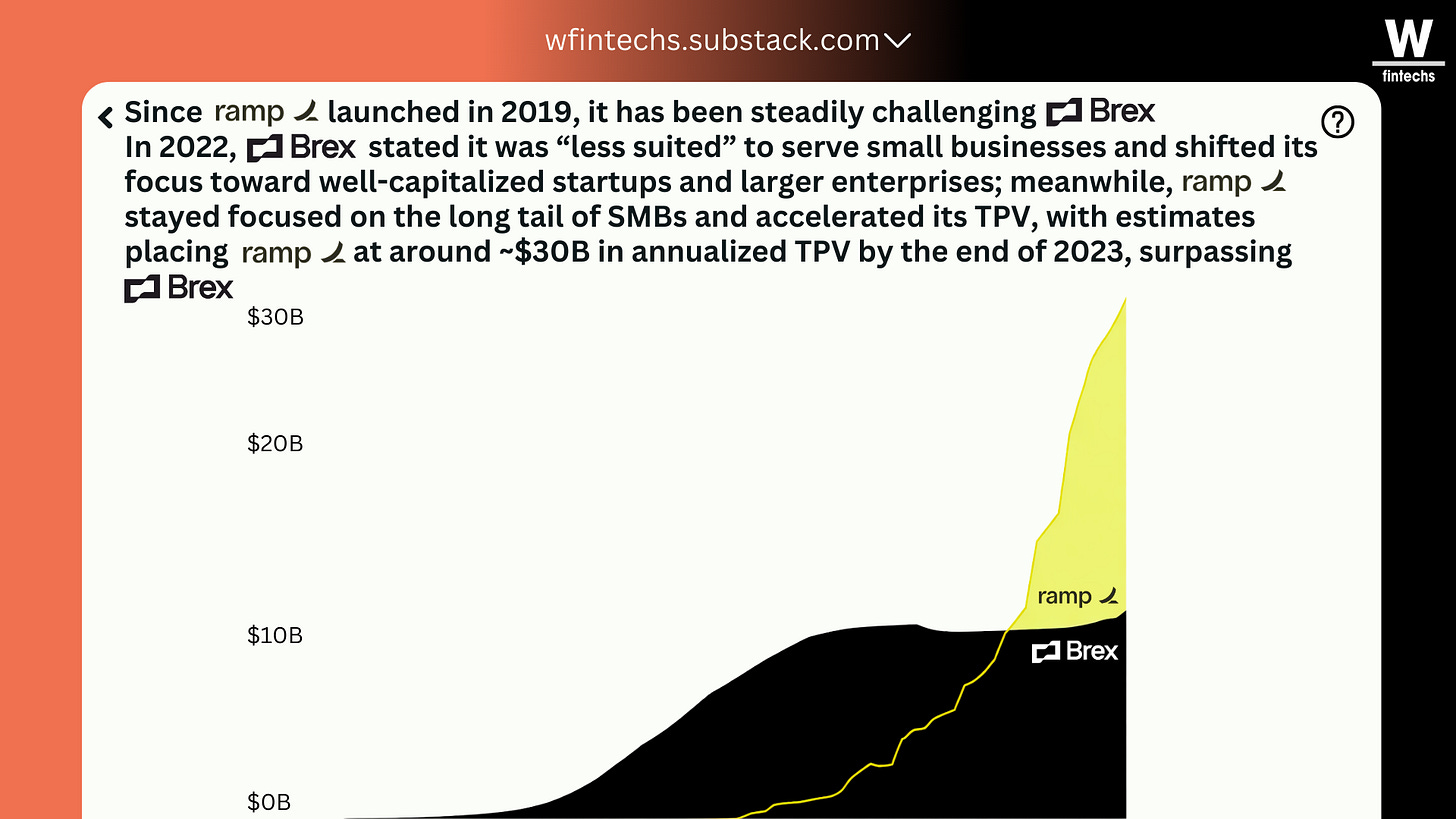

The attempt to serve a very broad base of small businesses ended up generating weak unit economics and service friction, leading the company to deliberately reduce its exposure to smaller customers in order to preserve focus and service quality, a move that opened space for competitors such as Ramp to gain relevance by focusing precisely on this underserved segment of the market.

Brex kept serving well funded startups and growing companies as a priority, while gradually expanding to larger and mid market clients, adjusting its value proposition and product capabilities to more complex financial operations needs.

If you’re enjoying this edition, share it with a friend. It will help spread the message and allow me to keep providing high-quality content for free.

The Achilles heel called Ramp

Just as Brex began to adjust its operational focus and pursue greater efficiency, another player that had emerged two years after Brex started to gain traction and create discomfort. Ramp, founded in 2019 in New York, entered the market with a thesis that, from the outset, sought to differentiate itself from the traditional corporate card narrative.

The founders realized that existing card issuers had strong, segmented specializations. Capital One focused on underwriting, American Express on rewards, and Brex on marketing to newly formed startups.

However, there was no company whose dominant focus was product and engineering in the construction of a corporate card solution. For them, this created an opening to design a financial technology company built on engineering and product principles, not merely on banking processes or reward incentives.

Instead of simply issuing cards, Ramp positioned itself as a financial operations platform aimed at reducing costs and manual work time, with automation and back office control as its core value proposition.

This focus became clearer as Ramp expanded its product scope beyond corporate cards. Ramp’s traction also contrasted with Brex’s moment of transition. In 2025, the company closed a new funding round valuing it at around US$22.5 billion, driven by a US$500 million investment, and later at approximately US$32 billion, with annualized revenue growth exceeding US$1 billion and a much larger customer base. This growth was accompanied by a strong narrative around operational savings and process automation, summarized in the promise to save companies time and money.

While Brex, after its 3.0 reorganization, repositioned itself to serve more mature and enterprise customers with a broader range of financial products, Ramp maintained a focus on reducing cost and labor time for finance operations teams, with tools that replace manual reporting, expense reviews, and slow approvals with automated processes that integrate directly with accounting systems and ERPs.

The challenges ahead

Even with operational improvements and a clear acceleration in revenue over recent quarters, Brex’s trajectory through 2026 reflects both achievements and the structural challenges of this market.

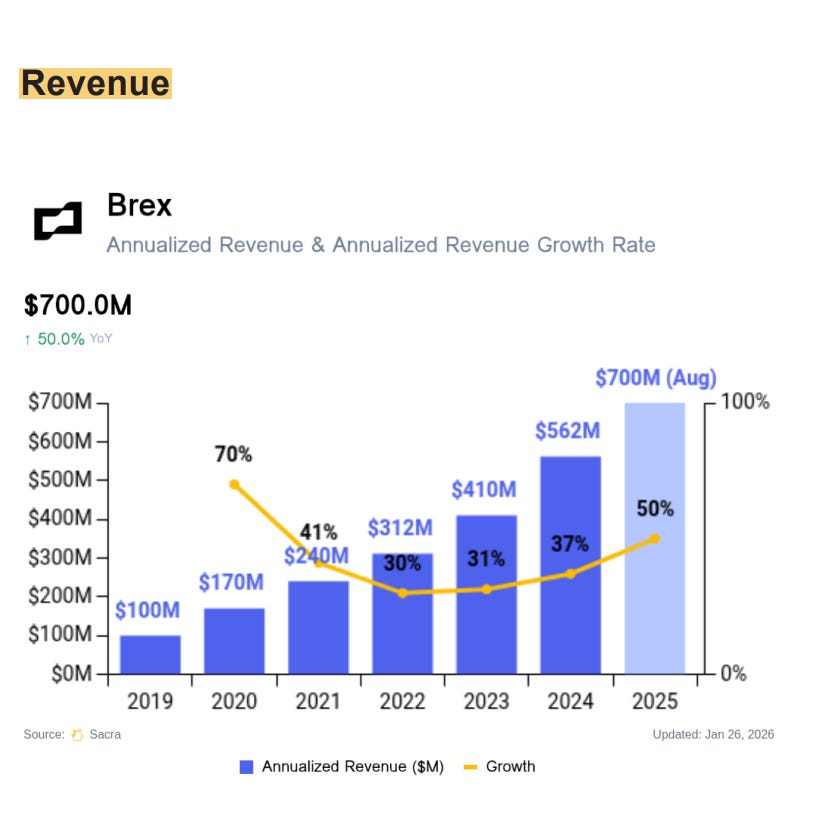

Between 2017 and 2022, the company moved from an initial valuation in the tens of millions of dollars to a peak of around US$12.3 billion. During this period, revenue estimates from Sacra indicate that Brex reached approximately US$700 million in annualized revenue by August 2025, with around 50 percent year over year growth, following a slowdown phase in 2022 and 2023. The path to profitability, however, was long and required successive strategic adjustments.

Brex’s valuation followed these shifts. After reaching its peak in 2022 at US$12.3 billion, many investors expected the company to continue scaling regardless of market conditions. However, in 2026, the sale to Capital One for approximately US$5.15 billion represented a figure substantially below its peak valuation.

Early investors who entered in 2017 achieved an estimated return of around 700 times their capital, one of the highest multiples in a recent venture capital cycle. In contrast, later stage investors saw returns below invested capital, particularly those who entered during rounds closer to the peak valuation cycle.

One thing is clear. Brex managed to build an impressive story in this market. One point Pedro highlighted in an interview was that a key foundation of the acquisition was the fact that Capital One is still led by its founder, Rich Fairbank, three decades after the bank’s creation, and that it is a systemically scaled institution that continues to operate with a long term vision, a strong appetite for technology, and a willingness to reinvent its own core. The budget is also significantly larger. Today, the bank operates with an annual budget of roughly US$6 billion in marketing and another US$6 billion in engineering and product, figures that fundamentally change the scope of ambition possible for Brex.

Even if the transaction value came in below what some investors expected, the union between the two companies has the potential to reshape the competitive dynamics of this market. Ten years separate the sale of Pagar.me to Stone from the acquisition of Brex by Capital One. Operating with the resources of a large bank significantly expands the platform’s reach and ambition, but it will also impose new kinds of pressure. Brex is now playing a much larger scale game. It will be interesting to watch how the financial stack of American companies may be redesigned by this combination.

If you know anyone who would like to receive this e-mail or who is fascinated by the possibilities of financial innovation, I’d really appreciate you forwarding this email their way!

Until the next!

Walter Pereira

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the author, Walter Pereira, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or clients of W Fintechs.

https://startups.com.br/la-fora/brex-e-zip-firmam-acordo-para-reduzir-queima-rumo-ao-ipo/

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2022-october-availability-of-credit-to-small-businesses.htm

https://www.brex.com/journal/a-message-from-our-founder

https://www.brex.com/journal/building-brex-3-0-march-2024

This piece really made me think about the journey, similar to finding that perfect flow in my Pilates routine, your insights into fintech's evolution are truly briliant.